THE NICKNAME the “Southern Part of Heaven” has been synonymous with Chapel Hill for several decades. Yet it’s not commonly remembered these days how that moniker came to be, nor its meaning. Last year while I was giving a talk for the Chapel Hill Historical Society about Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1960 trip here, I asked the audience how many knew the nickname’s origin. The crowd skewed retirement age, with an obvious interest in local history, but very few raised their hands.

The nickname’s source is a book titled The Southern Part of Heaven. When I asked if anyone had read it, barely any had. Given that this book had birthed a slogan of such longstanding civic pride in a place that loves to be in love with itself, you’d think that The Southern Part of Heaven would be for sale in every local bookstore, prominently displayed in every gift shop and knickknack store. But it went out of print about 50 years ago, and the nickname’s provenance has been memory holed. There’s a reason.

cw: racist language and images; suicide

THE SOUTHERN PART OF HEAVEN was a memoir by the illustrator William Meade Prince about his boyhood in Chapel Hill in the early 20th century. First published in 1950, the book was reprinted by UNC Press in 1969. Prince’s title took off as a town slogan with staying power, one employed for nostalgia and bragging, wielded to attract tourists, students, and donations. How could any place compete with heaven on earth?

Prince crafted the title from a perhaps apocryphal anecdote, which he retold in the book, from the deathbed of a prominent merchant. A.A. Kluttz owned a store on Franklin Street and lived in what is now the Delta Delta Delta sorority house. His store, a hub Prince likened to a local “Mecca,” sold just about everything. As Kluttz lay sick and dying in 1926, the Presbyterian minister visited. Sensing his time nearly up, Kluttz asked the minister what he thought Heaven would be like. It was a chilly, icy day. The minister paused and thought a minute. Then he replied, “I believe Heaven must be a lot like Chapel Hill in the spring.” Comforted, Kluttz drifted away to the thought. Prince coined the phrase the “Southern Part of Heaven” from the minister’s line.

If Prince had left his point there, that would be one thing. But Prince had a rather specific vision of heaven in mind. The story of Kluttz’s deathbed wasn’t even from Prince’s boyhood, the subject of the memoir; Prince was grown and gone by then. But Prince saw more than rhetorical material in the story. It was a useful tool for constructing a larger narrative.

PRINCE WAS an illustrator in the vein of Norman Rockwell who moved back to town as a successful adult. He spent the first few years of his childhood in Roanoke, Virginia; moved to Chapel Hill as a boy; worked in New York City for years; then returned to Chapel Hill. (Coincidently, I grew up in Roanoke, came to UNC for college, lived in New York, then moved back to Chapel Hill.)

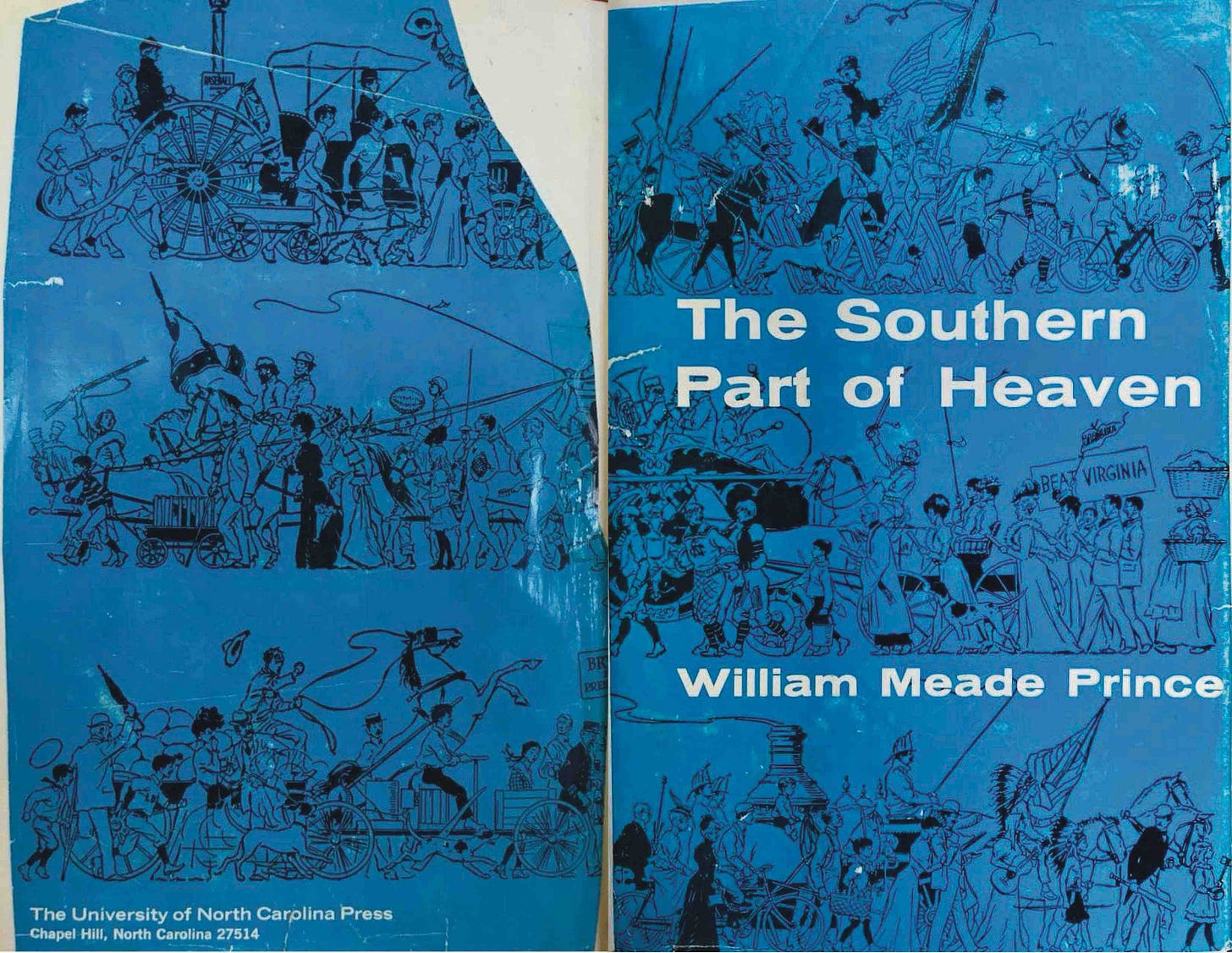

My copy of The Southern Part of Heaven is from the 1969 reprint, and the jacket cover happens to be glued inside. It features a Prince illustration of a parade that reflects the Chapel Hill characters and stories in his book. Already, there are issues.

The images include the Confederate battle flag, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, a mammy carrying laundry baskets on her head and hip, a Black man with a watermelon on his head, and kids wearing Native American costumes. There’s also a political sign for William Jennings Bryan for President. Bryan is considered by some to have been an early-day Donald Trump.

If the illustration looks a bit familiar, it is. The sketch has been displayed at the Ackland Art Museum fairly recently; similar Prince sketches were the basis for the Circus Parade wood carving now in the Alumni Center; and the style is similar to the Porthole Alley mural “Parade of Humanity.” But you know what they say about judging books by covers. So let’s open up The Southern Part of Heaven.

Part of the Circus Parade carving now in the Alumni Center, previously displayed in the Carolina Inn and the Monogram Club

Porthole Alley connecting Franklin Street to UNC's campusINSIDE, Prince takes until the second sentence to praise the Confederacy and use the phrase “superior beings” in reference to “masters.” The fourth sentence honors Robert E. Lee.

CHAPTER ONE

We were at the dinner table, that calm summer midday—my father, who was on one of his rare visits home, and Mother and Grandpa, and my uncles, Mars’ Phil and Mars’ Pike.

North Carolina, in 1900, must have been one of the only thirteen places where uncles and other superior beings were called Mars’—that beloved Southern abbreviation for Master (broad a’d Master) ; the other twelve, naturally, being the remaining sovereign states of the greatest nation on which the sun ever shone—or set—the Confederate States of America. It was a term of high respect and affection, meaning everything from Sir to Boss Man. The best known of all Mars’es, of course, was Mars’ Robert—the name given Robert E. Lee by his devoted followers.

Not a promising start. But the book was written 70 years ago. On the other hand, that was 85 years after the Civil War. Let’s keep reading…

Well, it turns out that first page was just scratching the surface of the Confederate hagiography and Lost Cause propaganda contained therein. Beyond the veneration of generals, great lengths were taken for glorifying white Southerners in general and placing them in sorrowful light, while demonizing Yankees. By no coincidence, another recurring theme was the Black people in Prince’s childhood who appear throughout as racist caricatures. Even the Black people he claimed to think of nearly as family he primarily saw as sources of labor, amusement, and ridicule.

Let’s look at more excerpts, in order of appearance:

Pages 19-20, Prince on his friend Wump, Prince’s “yes man.”

Behind us lived one of my best friends, Wump Whitted. He was a gangly colored boy, black as the ace of spades, a few years my senior, and he lived with his mother in a little one-room cabin on the edge of the woods. Surely he couldn’t have been christened Wump (or christened, for that matter), but Wump he was, and I never questioned it.

Pages 26-28, on John Atwater, who worked for Prince’s family — with illustration.

But I enjoyed the woodhouse the days Uncle John Atwater was out there chopping. He was not another real uncle, but the old colored man who did all sorts of things for us. He was one of the messiest tobacco-chewers I ever saw ; the juice would get all over his wrinkled, laughing old face and drop off his chin, because he had so few teeth, I reckon. He’d wipe the juice off with the back of his hand, and go on talking and chopping. He entertained me endlessly with fascinating stories of the time when he’d been a slave, and how, when he got E-mancipation, he’d gone off with the Yankees.

This business of E-mancipation was intriguing, and I pressed Uncle John for details.

“Well, I don’ know,” he’d say thoughtfully, scratching his head and leaning on his ax. “Hyah I wukin’ f’Mist’ Purefoy ’long time, an’ den d’man say, ‘You is E-mancipation’—and dere you is. Hit were like dat.”

“What happened then?” I’d ask.

“Hit were a mighty fine time,” said Uncle John. “Mist’ Purefoy he come an’ say, ‘John, you is E-mancipation.’ Den me an’ Mist’ Purefoy we shake han’s and he say, ‘G’bye, John,’ an’ I goes in d’town an’ dey was jes’ a singin’ an’ dancin’ an’ carr’in’ on. But byen’bye I goes back out tudda farm an’ Mist’ Purefoy he say, ‘Howdy, John. Ain’t you E-mancipation? You don’t hafta wuk no’ mo’ . . .’ Das d’way hit were.”

This explanation did not satisfy me. “But how . . . ?” I asked, “Everybody’s got to work !”

Uncle John smiled wryly and spat a rich stream. “Ya’ah,” he said, and chuckled. “ ’At a fac’. I fin’ hit out.” He left me with the impression that E-mancipation was something you had to look out for.

Pages 50-51, on what is now known as the Northside neighborhood.

… as you swung the big S curve through Sunset, which was the colored residential district, and passed the Potters’ Field, where the Potters lay. (The people buried there, I knew, were bums, and destitute, but I never understood why their resting place was known as Potters’ Field until I heard Dad, once, describe such a person as having “gone to pot.” Ever after that I thought of a human derelict, as Grandpa called them—as a potter. …

… Pickaninnies playing in the gutter straightened up and waved and danced as you pounded past, and some of them ran frenziedly along the sidewalk trying to keep abreast of the flying carriages. Black faces in the doors of little Negro stores flashed toothy grins at you as you hurtled by…

Page 58, only a short sampling on the years just after the Civil War.

Afterward came the Scalawags and the Carpetbaggers, and the University had to close its doors. The village was policed by Negro soldiers and the inhabitants looked out through shuttered windows, and the long, lean years of Reconstruction dragged along.

Pages 62-63, on the deification of Lee and Jackson. The latter part described the local schoolhouse about three-quarters of a century after the Civil War, after Chapel Hill and UNC had cemented their bona fides as the liberal beacon of the South.

I was brought up in the more or less unreconstructed atmosphere then general in the South. Erring children were told that the Yankees would get them, rather than the goblins, and it was a terrifying prospect. Quiet mourning for the Lost Cause, and veneration for its leaders, was almost a religion. In fact, in one instance I remember, it came right out in church. “The God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee,” was a phrase proudly hurled from the pulpit by Dr. Jones, the Baptist minister. …

In all the homes, and public buildings, too, there were pictures of Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Our picture of General Lee, one of them, was magnificent, a life-size steel engraving, in a heavy gold frame, which hung over the sideboard in our modest dining room, and I remember often gazing at his grave and noble face. Our picture of Stonewall Jackson, across the room, was almost as imposing. … Just a few years ago, when I came back to Chapel Hill after my long absence, I went one day to the elementary school, and there, in the auditorium, flanking the stage—the only pictures in the room—were portraits of this immortal pair.

Page 63, on Decoration/Memorial Day celebrations around the campus Confederate monument.

In North Carolina it is May 10th, and this was always a great and thrilling day. the village would be full of people from the countryside. There was always speech-making on the Campus, by the Confederate Monument, and the little college band played “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” and “Dixie.” The boys and dogs ran around and shouted and barked and rolled on the grass, while the old men got together in groups and brandished their canes and drew diagrams on the ground, and the ladies bustled about getting ready for the dinner served the veterans on long trestle tables under the trees. This came after the dusty pilgrimage to the Cemetery, with the band leading the way and playing “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” and the banking of flowers on the many soldier graves. The quiet little graveyard is now surrounded on three sides by the buildings and playing fields of the University, but still it blossoms out each Tenth of May with brilliant little Confederate battle flags flying once again over those unforgotten heroes.

Page 73, on his relatives’ house in Richmond, Virginia. The reprehensible term Prince used refers to what is now commonly called a “lawn jockey.” [redaction mine]

There are smart shoppes there now, and sleek motors line the curb where once the carriage blocks stood and the little n****r-boy hitching post before Uncle George’s door.

Page 90, on John Atwater again.

…my box of carpenter tools, the ’coon skin Uncle John Atwater had given me…

Pages 133-134, on kitchen servants.

[My mother’s] lack of culinary skill was not to her discredit ; always there was a slavey in the kitchen, that was an accepted fact of life and one you took for granted. Everybody had a cook. Even genteel poverty, if such was your lot, was not genteel unless you had a cook. Not that we were at all poverty-stricken ; we did all right. But it was just that any Southern lady of the period, even though she be as poor as Job’s turkey, had as soon be caught over a hot cook stove in the kitchen as without her corset cover.

Pages 183-185, on Jinny Johnson, who did the family’s laundry — with illustration.

In this boiling pot we brewed some weird concoctions, recipes given us by Aunt Jinny Johnson, whom we thought of as something of a witch doctor because she knew a lot of homely remedies and superstitious preventatives. Aunt Jinny was the old colored woman who did our washing. She was almost a member of the family, and Mother called on her for any and everything. We depended on Aunt Jinny as far back as I can remember. When I was very little she was the nearest approach to the Old Negro Mammy, beloved of song and story, that I ever had. Every Southerner of any consequence is supposed to have an Old Negro Mammy who held him on her lap and sang spirituals to him and called him Honey Chile, while the Darkies, down under the Plantation’s great, moss-hung trees, played banjos, and the people up in The Big House danced and gambled and drank. We didn’t have any of that—and I am overreaching myself when I claim Aunt Jinny as my Mammy, but I do remember well what a broad and comfortable lap she had, and how kind she was. …

She was a huge old woman, with a rugged, almost masculine face, which was covered by an eternal smile. She moved like a runaway truck, running over and scattering pickaninnies before her. Her arms were like a stevedore’s and her bosom like a feather bed.

Page 190, on the work ethic of some Black people. To introduce the point that he had always been a hard worker, Prince started chapter 17 with a lengthy meditation on what he saw as lazy behavior from others. It began:

Among the colored folk of the South and of that day there was a small minority born to rest. From the beginning, and all through their lives, they rested. Labor of any kind, for them, was akin to sin; they were touched by The Finger, and they were foreordained to rest. Even light or pleasurable endeavor, if calling for the expenditure of any energy, was denied them. They were chosen, upon whom the yoke of work was never laid. Their friends and relatives recognized their unique status, and provided for them bountifully. …

THE PROBLEMS are pervasive and defining. One might be tempted to think … well, those excerpts are bad, but they were of their time, nostalgia reflective of the era in which they were written … and well, that’s partly right. It was of its time. But probably not quite in the way you might think. Let’s look at those publishing dates again.

The Southern Part of Heaven first came out in 1950, when pushes to end Jim Crow were gaining steam post-World War II. UNC, for example, would have to admit its first Black students, into the law school, the following year due to a court order. Three years before The Southern Part of Heaven, the First Freedom Riders were terrorized in Chapel Hill during their Journey of Reconciliation. (It’s also worth noting that UNC Press published The Woman Who Rang The Bell, another book molding a local Lost Cause narrative, in 1949.)

Then nearly two decades passed, and the nation underwent drastic changes. Now look again at the timing of the reprint of The Southern Part of Heaven by UNC Press, in 1969, long after Prince’s death. It was on the heels of the civil rights gains that came from so much turmoil, progress that arrived quite reluctantly in Chapel Hill.

It’s clear from the illustrations and text that the Southern Part of Heaven, as a book and slogan, was a Confederate monument in the form of a moniker. It was a marker, a reminder of whom Chapel Hill belonged to. But like with Silent Sam, the explicit symbolism was later obscured and conveniently forgotten over the years.

In 1951, the year after his book first published, Prince died by suicide in his home in Greenwood, an early suburb community developed by the playwright Paul Green, one of Chapel Hill’s most significant liberal icons. Black people were barred from living in Greenwood by the neighborhood’s whites-only covenant.

For whom was the Southern Part of Heaven heavenly? Prince was clear in its meaning. The emphasis was on the Southern part, as defined by him and so many other white people here. It was the Confederate Part of Heaven. It was the White Supremacy Part of Heaven. Prince said so from his memoir’s first page. And the town enthusiastically adopted the slogan. Generational Black families here have always understood that this version of heaven excluded them though. That’s why, as Yonni Chapman wrote, they sometimes called Chapel Hill and UNC the “Southern Part of Hell” instead.

On the inside of the 1969 jacket cover for Prince’s book, glowing reviews were quoted from newspapers in New York and Chicago. Below them was also a quote from the Chapel Hill Weekly. It stated: “What I am trying to say is that while Mr. Prince’s book is a charming and doubtless a faithful picture of Chapel Hill sixty years ago, it is also a faithful picture of thousands of small towns all over our land sixty years ago.”

That is surely true. But Chapel Hill, henceforth, called itself Heaven.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

The Southern Part of Heaven by William Meade Prince (1969 edition)

This newsletter post was adapted from a thread by Mike Ogle: Twitter

“Martin Luther King Jr. and Chapel Hill’s Jim Crow Past” by Mike Ogle: News & Observer

William Meade Prince: NCpedia

William Meade Prince and Lillian Hughes Prince Papers collection overview: Southern Historical Collection

Remembering Chapel Hill: The 20th Century As We Lived It by Valarie Schwartz

“Etched in History” on the Circus Parade carving: UNC General Alumni Association

“Housing Segregation in Chapel Hill” by Mark Chilton: Piedmont Wanderings

“Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960,” doctoral dissertation by John K. (Yonni) Chapman, UNC-Chapel Hill (2006)

All book photos by Mike Ogle

William Meade Prince photo: Find A Grave

Hello, I just emailed the address listed in the about section. I am trying to get in touch with Mike. If you did not receive an email, please reply to this post. Thank you. Drew

In the book, included in the section on Jinny Johnson (pp.183-85), is a description of where she lived. If you head east on Franklin St. you can still make out the "brow of the long, winding hill as you start down the road to Durham." At the brow, on the right, there are several sections of huge boulders which could match the "huge boulder" mentioned by Prince as one of the "timeless and beloved landmarks" he would pass as a child on the way to the Strowd farm house and that were still there when he returned to Chapel Hill as an adult. "But the little cabin (Jinny Johnson's home) is displaced by fine residences now." So, it seems that you can still trace Prince's steps and more or less locate where Jinny Johnson's cabin used to be. The "huge boulder" that sat in front of her house still sit in front of the "fine residences" that "displaced" it.