AROUND 10 P.M. on a Wednesday, 155 years ago this week, a Chapel Hill mob of young white men nearly burned alive about 20 Black people. Enslavement had ended in the village five months before when Union troops arrived up what is now Raleigh Road and went door to door telling enslaved people they were free. To celebrate, one boy took a joy ride through town with soldiers on horseback. Like the story of that boy and others though, the near mass lynching is little known.

I first learned of the September 13 attack in Yonni Chapman’s dissertation, “Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960.” It gets one paragraph there because Chapman had so much ground to cover. But it seemed a big what if moment. What if the Black people who were terrorized that night hadn’t escaped? What if the post-Civil War era had begun with a mass murder by UNC students? How differently might the history and reputation of this place look? I’d always wanted to look into the events of that night, so I did this month.

A GROUP of approximately 20 Black people had gathered on the night of September 13, 1865, to select delegates for the upcoming Freedmen’s Convention in Raleigh. The white men who violently broke up the political meeting surely saw it as a threat to power.

The footnote in Chapman’s dissertation mentions four sources: a master’s thesis, two books, and a letter of correspondence archived at Duke. Due to COVID, I couldn’t access the archived letter, but it is a primary source behind the description in the thesis, which Chapman heavily leans upon in his account.

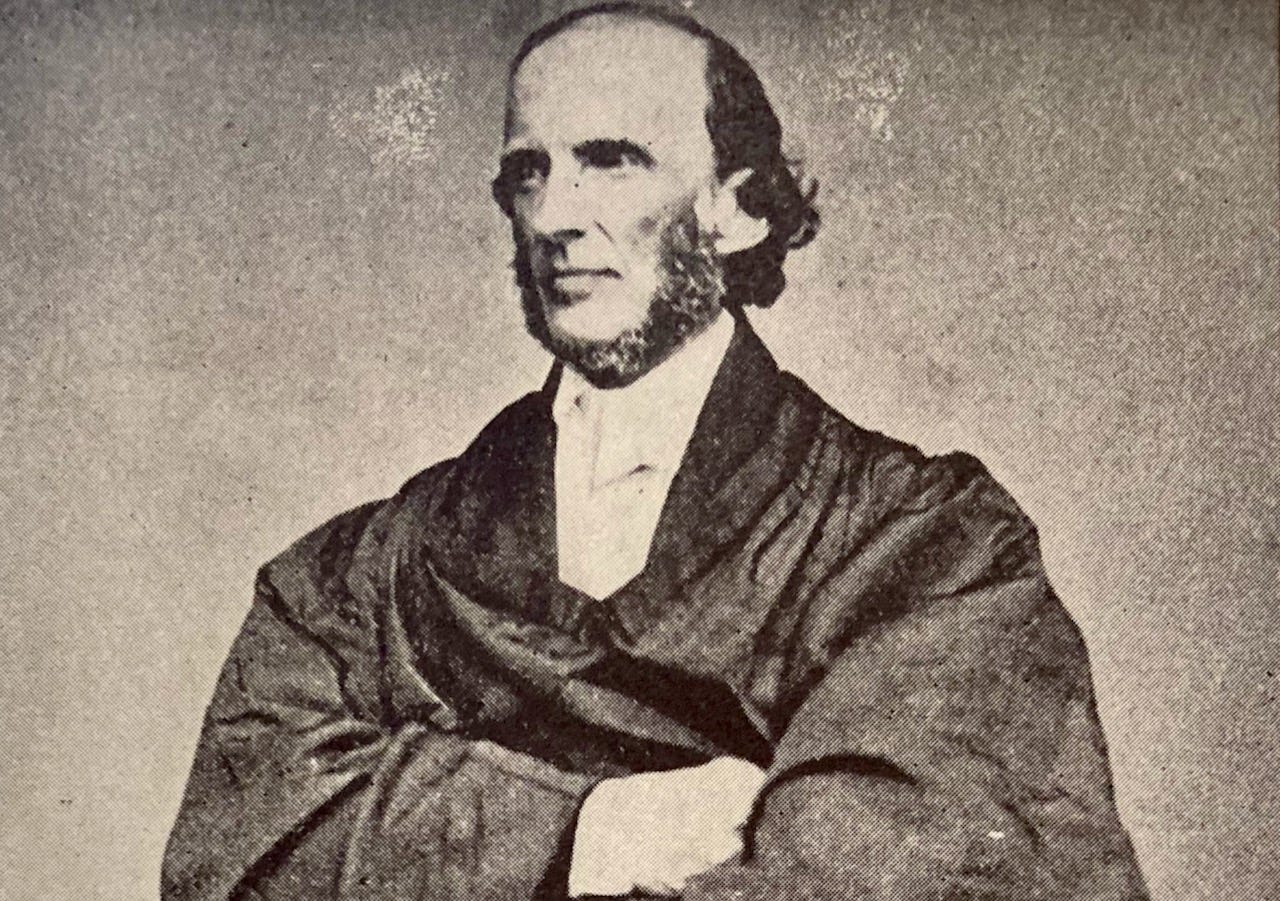

The letter was written by Henry Clay Thompson, a UNC alum who’d stayed in the area after college, the day after the attack. He sent it to Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick, a former professor from Thompson’s time as a student. UNC had fired Hedrick in 1856 for expressing anti-slavery views. (The thesis author also cites a letter by a UNC student, Edwin Wiley Fuller, to his father, but I was unable to locate Fuller’s papers, which had been archived at Duke at the time of the 1961 thesis.)

Professor Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick, cancelled by UNC in 1856The account offered in the thesis emphasizes the supposed “secrecy” of the political meeting as a way of victim-blaming the Black people attacked by the mob. The thesis states:

Negroes in Chapel Hill met to elect delegates on the night of September 13, 1865. Most secretively, they gathered in the second story of a building in the village where they were to hear a special speaker from Raleigh. At approximately ten o’clock, students from the University of North Carolina rushed across the campus yelling and pelting the meeting house with stones. They tore down the outside stairs, trapping about twenty Negroes on the second floor. Replacing the steps with ladders, students rushed into the building with sticks. They were repulsed, but their bloody faces infuriated those gathered below, and cries of “fire to it” arose from the angry crowd. The mob was soon quieted, but not before twenty frightened Negroes had jumped from the second floor windows and fled. These Negroes intended no harm, yet whites overhearing whispered plans concluded, as did one student, Edwin Fuller, that their secrecy was a cloak for insurrectionary proceedings.

At that upcoming Freedmen’s Convention, the asks were far from sinister: ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, the rights to vote and to testify in court and serve on juries, protection, and legislation regulating wages and working hours to help prevent former enslavers from abusing them.

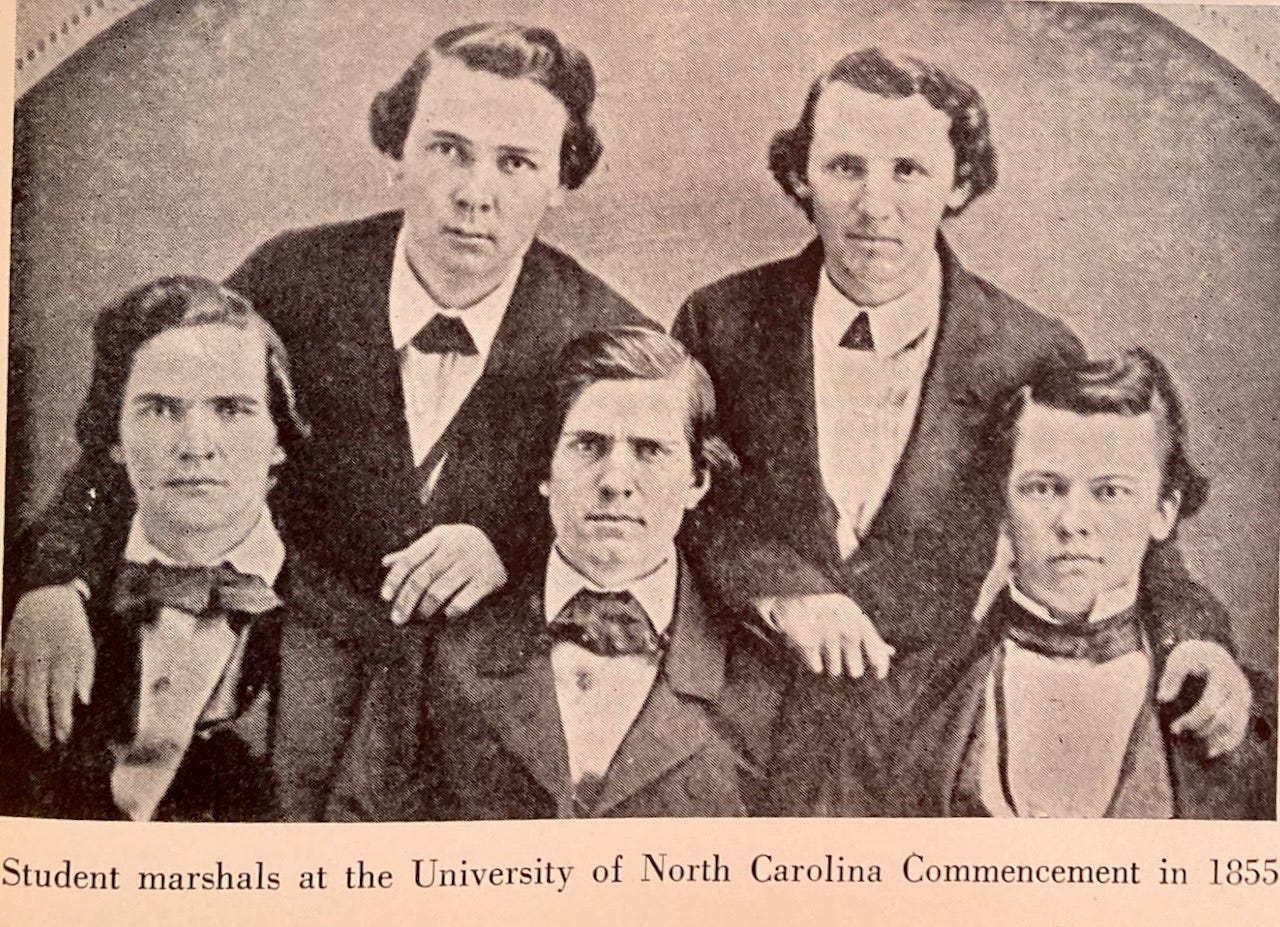

Mid-19th century UNC students, before the Civil WarThe 1985 book Chapel Hill: An Illustrated History also mentions the bloody confrontation, albeit briefly. In the 198 pages, it gets three sentences that frame the opposing sides as equal actors and concentrates on white fears. James Vickers writes that students “got into a row with a group of freedmen assembled to elect delegates to a civil-rights convention in Raleigh. Several people were injured in this the first of Chapel Hill’s two race riots, and villagers assumed that a Negro guard would be placed on the university. That in fact later came to pass.”

The nearly tragic event also gets mentioned in passing in The Woman Who Rang The Bell, a book about Cornelia Phillips Spencer. Spencer played a starring role in shaping the time of Reconstruction and so-called Redemption in Chapel Hill, including the closing and eventual reopening of UNC. Her influence and writings helped define the era’s lasting narrative.

According to the biography, Spencer described the bloody assault as a “muss” involving the “young white men of the town and college and the Negro freedmen.” Again, Spencer does not assign blame. Spencer further writes in her journal: “There was a general row on the occasion. Some heads and arms broken etc. Many fear the result will be the Negro guard will be sent up here.” She also explains that her interest in the near mass lynching is a purely political one.

One thing historians who write of Elizabeth of England insist upon as striking in her character—she knew how to give graciously when she found concession on her part was inevitable. She made a favor which was about to be extracted from her by the people, appear as if it was her own free bounty. I think Southerners might take a hint from this policy in their present position with regard to the Negroes. We ought to treat them graciously, kindly, and have the air of bestowing on them that which we know we will have to give them. Not free suffrage, I have no idea they will or ought to have that, but certain little rights and privileges which mark the free man. Let us cheer them on in their poor attempts to assert themselves, and keep them as friends.

I have no sort of patience or sympathy with such squabbles as were gotten up here a fortnight since. The boys have not been punished and no ill effects have ensued, but I really despise such conflicts in which Southerners have everything to lose and nothing to gain.

Spencer’s concern is callous and cynical: How did the incident potentially harm the preservation of white supremacy? How could white Southerners instead pretend to be magnanimous for advantage?

Shortly after Union troops had arrived at Easter, Spencer wrote in her journal: “The whole framework of our social system is dissolved. The Negroes are free, leaving their homes with very few exceptions, and the exceptions are only for a time.” Five months later, she still understood the fragility of that social order. But she also saw that white supremacy could be preserved even in the absence of enslavement.

Chapel Hill's post office building around the turn of the 20th century, on the site of the current post office building and Peace and Justice Plaza, showing what downtown buildings might’ve looked like in the time of the near lynching.THE STORY best known from that time in Chapel Hill is the well-worn tale of the scandalous wedding between the university president’s daughter and the occupying Yankee general. Like the Black political meeting, the romance was seen by white people as a threat to their social order, a treasonous one that must’ve filled fainting couches across the village. Invitations were spit on and the affair was lightly attended. UNC students hanged the university president and groom in effigy and disruptively rang the college bell through the ceremony.

Eleanor Swain and Gen. Smith Dykins AtkinsIt’s easy to imagine that three weeks later, in a time when lynchings were prevalent and violence was accepted, that a mob of UNC students could’ve followed through on their threats of fire after attacking with rocks and sticks Black people holding a political meeting.

The attack was part of a pattern of terror, violence, and murder across the South aimed at extinguishing the embers of Black rights. During the post-war years, President Andrew Johnson sent a Union general to survey conditions in the South. He wrote: “I saw in various hospitals negroes, women as well as men, whose ears had been cut off or whose bodies were slashed with knives or bruised with whips, or bludgeons, or punctured with shot wounds. Dead negroes were found in considerable number in the country roads or on the fields, shot to death, or strung upon the limbs of trees. In many districts the colored people were in a panic of fright, and the whites in a state of almost insane irritation against them.”

The Chapel Hill area was a center of Ku Klux Klan organizing and violence. By the 20th century, white supremacists had won and installed Jim Crow. It was the victory both the Klansmen and Spencer had envisioned. To celebrate and affirm, the Confederate monument was installed and several campus buildings were named for men who’d led or supported the Klan’s mission.

When Julian Carr bragged in front of the governor and university president of horsewhipping a Black woman just after the war, he was harkening back to when violence kept the white order in town. Now laws largely did the work for them. The monument’s erection signaled that the longterm project of white supremacy had succeeded … thanks to a combination of violent terror and the sort of political acumen Spencer advocated.

Right alongside, the university constructed its liberal reputation. But what if those students calling for fire on the night of September 13, 1865, had gotten their wish?

SOURCES & CREDITS:

“When the Confederacy Lost Chapel Hill” by Mike Ogle: Jackson Center

Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938

“Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960,” doctoral dissertation by John K. (Yonni) Chapman, UNC-Chapel Hill (2006)

Chapman’s footnote: From Henry Clay Thompson to Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick, 14 September 1865, in Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick Papers, Duke University Library, quoted in Jones, “Opportunity Lost”, 47-8. For an account of this event that dates it in the same week as Ellie Swain’s wedding, rather than September 13, see Vickers, Chapel Hill, 76. For Cornelia Phillips Spencer’s commentary on this event, see Russell, Bell, 76.

“Freedmen’s Convention”: NCpedia

“An Opportunity Lost: North Carolina Race Relations During Presidential Reconstruction,” master’s thesis by Bobby Frank Jones, UNC-Chapel Hill (1961)

Chapel Hill: An Illustrated History by James Vickers (1985 edition) [Note: This book was repackaged in 1996 as Images of America: Chapel Hill, a significantly condensed version of photos with captions.]

The Woman Who Rang the Bell: The Story of Cornelia Phillips Spencer by Phillips Russell (1949)

History of the University of North Carolina, Volume I by Kemp Plummer Battle

“The New Reconstruction: The United States has its best opportunity in 150 years to belatedly fulfill its promise as a multiracial democracy.” by Adam Serwer: The Atlantic

Photograph of books: Mike Ogle

Photographs of Hedrick, mid-1800s UNC students, and old post office: The Woman Who Rang The Bell

Photograph of Cornelia Phillips Spencer: Encyclopedia of UNCG History

Photographs of Swain and Atkins: Chapel Hill: An Illustrated History