SHORTLY AFTER Stone Walls launched, a tipster sent along a photo she’d recently taken of something that caught her eye: the back of the West End Wine Bar building on West Franklin Street. When I saw it, I had the same thought she did.

For those who don’t know, Colonial Drug Co. was a store and restaurant there for decades and the site of the first sit-in in Chapel Hill in 1960. The Chapel Hill Nine, as they are now known and celebrated, were Black teenagers from segregated Lincoln High School who walked into “Big” John Carswell’s establishment, sat in the booths, and refused to leave. Carswell knew them well — they were regulars — but Black customers could only buy food to go. They could not dine-in. Many businesses in Chapel Hill and Carrboro were for “Whites Only.”

What the tipster and I suspected was that before integration Black patrons had to enter and exit Colonial Drug through that back door, which faces the historically Black Northside neighborhood. We wondered if “COLORED” had once been above where “ENTRANCE” still existed.

I went to take a closer look but saw no evidence that a word had been erased from the brick. So I called upon the expertise of one of the Chapel Hill Nine. He said it was not the case that they had to use the back door. Nevertheless, looking at the fading white paint of COLONIAL DRUG CO. felt a bit like seeing a ghost to me.

(Nearby, the back of Carolina Brewery also reveals an echo from the past, the Johnson-Strowd-Ward furniture company.)

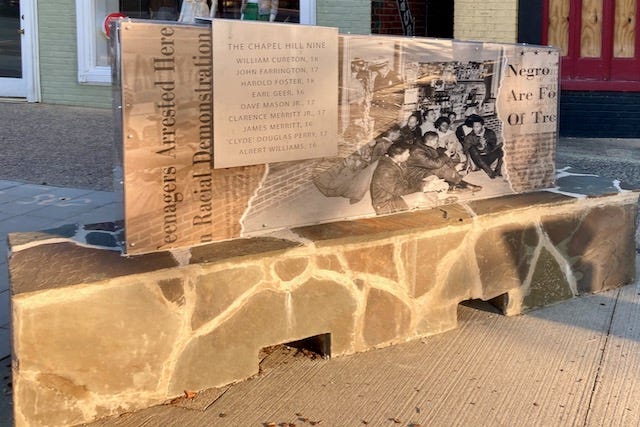

Ghosts are all around, and they’re becoming more visible, which is a positive development. This past February, on the 60th anniversary of that first sit-in, the town unveiled a marker out front for the Chapel Hill Nine in a large ceremony that closed Franklin Street. The monument was created by Stephen Hayes, the Durham artist also behind the incredible Cash Crop exhibit.

The Woolworth sit-ins in Greensboro at the start of February in 1960 sparked a wave of similar civil disobediences and demonstrations across North Carolina and the South aimed at public accommodations. On February 28, the Chapel Hill Nine brought that movement to Chapel Hill, a smaller town than most seeing uprisings. They were also exceptional in that they were only in high school. Imagine the courage required to put the words from their discussions around a neighborhood rock wall into that action.

They were:

William Cureton, 18

John Farrington, 17

Harold Foster, 18

Earl Geer, 16

Dave Mason Jr., 17 (below, second from left)

Clarence Merritt Jr., 17

James Merritt, 16 (far right)

“Clyde” Douglas Perry, 17 (second from right)

Albert Williams, 16 (far left)

Two months after their first sit-in, Martin Luther King Jr. came to town for a series of public talks. His first stop was the Negro Community Center to encourage those young people, already frustrated with the town’s stubbornness. Hundreds packed inside to listen. “You are demonstrating a magnificent act, a magnificent act of non-cooperation with the forces of evil,” King told them. “You are not seeking to put stores that practice discrimination out of business. You are seeking to put justice in business. Tell the businessman, ‘You respect our dollars; now respect our persons.’”

That period of local history has gotten a lot more attention since the Freedom Fighters’ Gateway was installed in 2017 and introduced at the annual Northside Festival organized by the Marian Cheek Jackson Center.

Mayor Pam Hemminger then formed the Historic Civil Rights Commemorations Task Force to document that history, leading to endeavors such as the Chapel Hill Nine Marker, a podcast series, a website, trading cards, and three bus shelters downtown with powerful movement photographs. One features leader Harold Foster’s memorable line: “Man, this town is hard to crack. It’s called a liberal place, but that’s a mirage man. When you go to get water, you just get a mouthful of sand.”

All the attention is more than I would’ve guessed we’d see just a few years ago. Hopefully it’s only a beginning, and a continued awakening to an oppressive history will impact local decision-making — by the towns and university, but also by individuals. (As this recent article details, white liberals are often the biggest impediment to racial progress, in spite of good intentions.)

The early 1960s movement shocked a lot of Chapel Hill’s white folks. Many had assumed their Black neighbors had it good compared to the South at large and viewed the demonstrators as ungrateful. But an acknowledgment of that disconnect has often been missing in the public talk about that period here. Although the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Chamber of Commerce did apologize for its significant role in fighting against those demonstrators more than 50 years later.

Rightly, the focus has centered the Black people who bravely struggled and fought. But what tends to get left out of these remembrances is the fact that their four years of sacrifice and anguish did not win their initial goal. Chapel Hill inflicted and witnessed the horrific things they went through — the indignities, hundreds of arrests, threatened family livelihoods, getting doused by bleach and ammonia, being urinated on — and its white people said no. Time and again. They heard the message loud and clear yet declined to ensure their right to eat where they pleased.

During the movement, not all businesses were segregated, and more voluntarily integrated as it went on. Much of the resurgence of that period’s history stems from Jim Wallace’s powerful photographs, which he discovered decades later. Wallace died in June, but when I interviewed him a couple of years ago, he mentioned that in those days the Daily Tar Heel staff hangout was Harry's, where Four Corners is now, because it was integrated. They often saw movement organizers there after demonstrations.

But many places remained segregated, and Chapel Hill refused to integrate as a matter of policy. It was not until the federal government forced the town, with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that the Chapel Hill Nine, by then in their 20s, got the simple freedom they’d sought in their liberal town when they’d sat down in Colonial Drug four and a half years earlier.

That systemic and institutional nature is important to remember too. As years go by, movements get looked back upon with civic pride without examining too deeply the collective shame that made them necessary.

In evoking King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, white people typically miss its point. Dreaming that his children might one day “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” was not a call for color blindness. Quite the opposite. That specific part of King’s dream was an idealized, distant endpoint that might one day result from true reckoning.

The thesis of King’s speech was this: “In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.”

King is now widely beloved and, like the Chapel Hill Nine, has a monument near the site of one of his most famous moments. Similarly, he too was not so popular in those days. He was assassinated at the age of 39, and he was far from alone in that fate. Having John Lewis for 80 years was too uncommon a blessing.

So when a white, Democratic ex-president makes a snide remark about Stokely Carmichael at another movement leader’s funeral, consider what the prevailing opinion must’ve been like back then. At the time of King’s death, 75% of white Americans disapproved of him too.

When news broke in 1968 that King had been murdered — eight years after the first Chapel Hill sit-in and four years after the forced integration of Colonial Drug — white UNC students cheered in the dorms.

WANT TO know more about that struggle in Chapel Hill? Lots of great resources are available, both in small bites and large:

A short video about the Chapel Hill Nine by the Historic Civil Rights Commemorations Task Force

Videos of an interview with the living members of the Chapel Hill Nine

HCRC Task Force timeline of events and a full list of sources

“Re/Collecting Chapel Hill” podcast series

Courage in the Moment, a coffee table book collection of Jim Wallace’s stunning photographs from his Daily Tar Heel days during the early 1960s movement

The Free Men by John Ehle, an important and revealing book especially useful because it was reported and written contemporaneously by someone on the ground, but also flawed because it centers the white UNC students in the movement

“Second Generation: Black Youth and the Origins of the Civil Rights Movement in Chapel Hill, N.C., 1937-1963,” John K. (Yonni) Chapman’s master’s thesis, a needed course-correction to the flaws of The Free Men. Those UNC student activists later said they were miscast in Ehle’s book as the movement’s leaders but they were more spokesmen for Harold Foster’s leadership. The thesis is not digitized, but perhaps UNC Libraries will do that soon.

“Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960,” Yonni Chapman’s doctoral dissertation, essential reading on local Black history

Oral history interviews on file with the Marian Cheek Jackson Center and the Southern Oral History Program

Yonni Chapman's Papers, archived at the Southern Historical Collection, contain many digitized interviews, photographs, and other materials

PART II of Stone Walls’ recent edition, “Police Problems,” is still in the works. Have any suggestions for historical or more contemporary examples of local police problems? Leave a comment or write me at stonewalls1793 at gmail.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

Chapel Hill Civil Rights Commemorations Task Force: chapelhillhistory.org

Martin Luther King Jr. in Jim Crow Chapel Hill: newsobserver.com

Chapel Hill bus shelters: chapelhillarts.org

“White liberals’ dangerous hypocrisy on race”: cnn.com

Chamber of Commerce apologizes: dailytarheel.com

Jim Wallace obituary: dailytarheel.com

“I Have a Dream” speech: kinginstitute.stanford.edu

Bill Clinton on Stokely Carmichael: washingtonpost.com

Harris Poll on Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968: theharrispoll.com

UNC students cheering at Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination: lib.unc.edu

Photos of backs of former Colonial Drug and Johnson-Strowd-Ward: Mike Ogle

Photo of Chapel Hill Nine Marker: Mike Ogle

Photo of living Chapel Hill Nine members: screenshot from Chapel Hill Historic Civil Rights Commemorations Task Force video

Martin Luther King Jr. headline and quotation: photo by Mike Ogle of the May 9, 1960 Chapel Hill Weekly front page, taken at the Chapel Hill Historical Society

Photos of Freedom Fighters’ Gateway: Mike Ogle

Photo of bus shelter: Mike Ogle

My family owned that building. E. A. Brown and later, Madeline Brown Wheless. I graduated from Chapel Hill High, 1966. It was the 1st year we were integrated. I had one young man in one class. Both his name and the class are forgotten now. (Names were never my forte!) I never knew about the sit in at the Colonial Store, until very recently. Thank you. I have Blackwood, Cheek, LLoyd and King relatives that settled Orange County. That was on the maternal side. My paternal side were in Edgecomb, and Nash counties in eastern NC. Rocky Mount. I have figured we had a few enslaved people and I have done some research. It is not easy work, emotionally or otherwise. Thank you for your journalism that helps us realize more about the past.