“HISTORY DOES NOT REPEAT ITSELF, BUT IT RHYMES.” That well-worn line, or some variation of it, is often attributed to Mark Twain, although there’s not much evidence he ever wrote or said it. The degree to which it rings true remains nonetheless if you read even a touch of history and turn on the news from time to time.

Speaking of the news, you probably heard about the big story that Joe Killian and Kyle Ingram at NC Policy Watch broke yesterday, that UNC had decided not to grant tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones for her appointment as the Knight Chair in Race and Investigative Journalism, a tenured professorship, in the UNC journalism school. There’s a lot of meat to their story, but essentially it boils down to political reactionaries and the radical right-wing turn the state legislature, UNC Board of Governors, and UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees have taken thanks to extreme gerrymandering. Also, the repeated capitulation to those forces. Grossly inequitable power structures. Fear of truth. And yes, racism and white supremacy.

NC Policy Watch reported: “Last summer, Hannah-Jones went through the rigorous tenure process at UNC, [Susan] King [dean of the journalism school] said. Hannah-Jones submitted a package King said was as well reviewed as any King had ever seen. Hannah-Jones had enthusiastic support from faculty and the tenure committee, with the process going smoothly every step of the way — until it reached the UNC-Chapel Hill Board of Trustees.”

Thirty-five members of the journalism school’s faculty have since signed a letter demanding “explanations from UNC’s leadership at all levels.” Presented with an opportunity to do so, the chancellor exited through a side door after yesterday’s Trustees meeting instead.

Hannah-Jones, of course, is the acclaimed reporter of The New York Times Magazine and winner of a Pulitzer Prize, a MacArthur Fellowship (aka Genius Grant), and a Peabody Award, among others. She is also the creator of the 1619 Project, which is what has made her such a focal point for conservative disdain. Since first published in 2019, the 1619 Project has been recalibrating the general public’s narratives around American history to place slavery closer to its center, as was always the reality whether we obscured it or not.

More locally, the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting, which Hannah-Jones co-founded, has received a home at UNC’s journalism school; UNC honored her as a Distinguished Alumna; she entered the North Carolina Media and Journalism Hall of Fame; and UNC has enthusiastically touted her in events and promotions during a time when the school’s treatment of Black people has been called into repeated and loud question.

That this tenure denial was happening at the same time that UNC was once again feting itself as the “University of the People” at its graduation ceremonies and while Hannah-Jones was being awarded an honorary doctorate at Morehouse College, an HBCU, is poetry so sad it requires no commentary.

SPEAKING OF HISTORY RHYMING, there is of course precedent for this sort of racism dominating faculty decisions at UNC. The example that came most immediately to mind occurred at another pivotal moment in American and North Carolina history during the lead-up to the Civil War.1

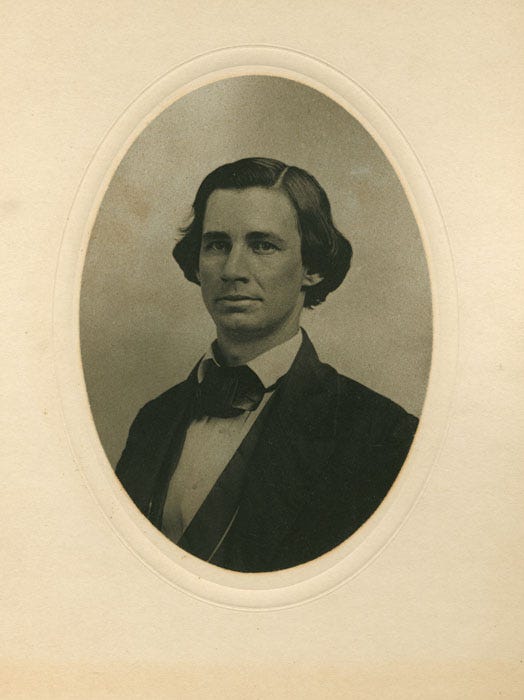

In 1856, with the United States fiercely divided over whether slavery should be allowed in its expanding territories, UNC dismissed Benjamin Hedrick, a young chemistry professor. His fireable offense was daring to honestly answer whom he would vote for in the upcoming presidential election when a student asked. That led to his having to publicly defend his preference, explaining that he thought slavery should not expand and therefore he would vote for the Republican candidate whose party also opposed it.

This piece titled “Professor Hedrick’s Defence” in the UNC Libraries exhibit “Slavery and the Making of the University” provides a well-documented explainer of the controversy that led to Hedrick’s firing.

It all began when, leaving the polls at the state election in August, he met several students who questioned him about the upcoming presidential election. “One asked whether if there were a Fremont ticket [Hedrick] would support it.” Hedrick said he would. Another asked “whether in case the South were attacked by [the] North” he would support the North. Hedrick said no.

Rumors began to circulate that Hedrick's opinions were more radical than they really were.

From that minor interaction, contempt boiled around North Carolina. People started publicly calling for the termination of teachers with “black Republican opinions.” (There’s a book for sale on Amazon called A Traitor and a Scoundrel: Benjamin Hedrick and the Cost of Dissent and it can be yours for $907.99.)

Hedrick responded to the criticism by explaining his beliefs in print. He began his letter in The North Carolina Standard with words that could just as easily be written today: “Now, politics, not being my trade, I feel some hesitation in appearing before the public, especially at a time like this, when there seems to be a great desire on the part of those who give direction to public opinion to stir up strife and hatred, than to cultivate feelings of respect and kindness. But, lest my silence might be misinterpreted, I will reply, as briefly as possible, to this, as it appears to me, uncalled for attack on my politics.”

Hedrick went on the explain his intent to vote for John C. Frémont, a Republican originally from Georgia who opposed slavery but had also committed acts of genocide against Native Americans in massacres in California. Hedrick wrote that he supported Frémont for two primary reasons: Frémont was a good, noble, and dedicated man and the “conqueror of California” as Hedrick noted Frémont’s own opponent James Buchanan had put it; and Frémont opposed the extension of slavery, the “right side of the great question which now disturbs the public peace.”

Similar to Hannah-Jones in her work on the 1619 Project, Hedrick raised the Founders in his letter, although his view did differ from that of Hannah Jones. He asked that we take a closer look at the deep, uncomfortable questions about slavery that had vexed the Founders at the nation’s birth, and their admissions of its evils even as they practiced them. Hedrick wrote:

“Opposition to slavery extension is neither a Northern nor a sectional ism. It originated with the great Southern statesmen of the Revolution. Washington, Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Madison, and Randolph were all opposed to slavery in the abstract, and were all opposed to admitting it into new territory. One of the early acts of the patriots of the Revolution was to pass the ordinance of ‘87,’ by which slavery was excluded from all the territories we then possessed. This was going farther than the Republicans of the present day claim.”

Hedrick quoted Thomas Jefferson and Henry Clay. He also directly addressed the writer of the anonymous attack signed by “Alumnus.” Hedrick’s careful words to this outraged person calling for his firing echo today’s environment of conservatives actually pursuing a high-stakes cancel culture on campuses — like blocking tenure for Hannah-Jones or literally outlawing the teaching of critical race theory or kneecapping UNC’s Center for Civil Rights or shutting down UNC’s Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity — while liberals in academia typically take more measured tones.

“If ‘Alumnus’ thinks that Calhoun, or any other, was a wiser statesman or better Southerner than either Washington or Jefferson, he is welcome to his opinion,” Hedrick wrote. “I shall not attempt to abridge his liberty in the least. But my own opinions I will have, whether he is willing to grant me that right of every freeman, or not.”

Hedrick’s letter even touched on the subject of one of the most controversial (but not really) passages from Hannah-Jones’s Pulitzer-winning 1619 essay: the role of slavery as a motivating factor in the American Revolution. Hedrick seems to have been a starry-eyed captive of the same strain of romanticism that has always softened the abject horrors of our chattel slavery system and its centrality to our society and economy still. “Our fathers fought for freedom, and one of the tyrannical acts which they threw in the teeth of Great Britain was that she forced slavery upon the Colonies against their will,” Hedrick wrote.

Shortly after publication of Hedrick’s letter, UNC’s faculty and UNC’s Board of Trustees, whom Hedrick had called “men of integrity and influence” who “have at heart the best interests of the University” in the letter, voted to fire him. In a private letter, Hedrick noted that professors’ expressed opinions on politics or even on slavery in particular had not been cause for dismissal before.

James Buchanan soon won the 1856 election. He visited UNC’s campus while the sitting U.S. president, speaking at its 1859 commencement in Gerrard Hall about the need to stand up for the ideals of the U.S. Constitution. Today, Buchanan is widely considered to be one of the worst presidents — often ranked the worst — in U.S. history.

The big irony here between 1856 and 2021 that goes back to 1619 is that Nikole Hannah-Jones is now such an object of scorn because she tells the truth about history, and yet her work is one of the brightest living examples of UNC’s professed values.

Lux, libertas — light and liberty — is on UNC’s seal and is the centerpiece of its mission and values statement. They are the “founding principles.” According to itself, “the University has charted a bold course of leading change to improve society and to help solve the world’s greatest problems.”

History’s rhymes get louder. Louder and louder and louder still. So loud now since 1793 that it’s becoming impossible not to hear.

ACTION ITEM:

The Carolina Black Caucus, in partnership with the Chapel Hill-Carrboro NAACP, is holding a rally at 8:15 a.m. today, Thursday, at the Carolina Inn to oppose the denial of tenure for Nikole Hannah-Jones.

ONE GOOD THING:

The Draft Air Permit that UNC’s coal power plant has up for renewal got more press coverage in addition to the last edition of Stone Walls, in the Daily Tar Heel, the Indy, the Local Reporter, and Chapelboro (via the UNC Media Hub out of the journalism school).

Amid that attention and public pressure, the mayor of Carrboro — with unanimous approval from Carrboro’s town council — as well as Chapel Hill’s mayor and town council submitted public letters opposing the proposed air permit as is. Carrboro council member Sammy Slade even simultaneously attended the remote public hearing about the Draft Air Permit and Carrboro’s remote council meeting in which Carrboro’s letter was approved. Slade had to mute his microphone in the council meeting to read Carrboro’s letter, hot off the press, during the Division of Air Quality hearing.

No decision on the Draft Air Permit’s approval has been announced yet.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

“PW special report: After conservative criticism, UNC backs down from offering acclaimed journalist tenured position”: NC Policy Watch

The 1619 Project: New York Times Magazine

“Professor Hedrick’s Defence”: Slavery and the Making of the University, UNC Libraries

“Stunned: UNC Hussman Faculty Statement on Nikole Hannah-Jones”: Medium

“Pulitzer Prize-winning MacArthur ‘Genius’ Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times to become Knight Chair in Race and Investigative Journalism”: UNC Hussman School of Media and Journalism

“Pulitzer Winner Hannah-Jones Returning to Join UNC Faculty”: Carolina Alumni Review

“Benjamin S. Hedrick (1827-1886)”: Documenting the American South, UNC Libraries

“Horace Williams House”: Preservation Chapel Hill

“Mission and Values: Lux, Libertas — Light and Liberty”: UNC-Chapel Hill

Frank Porter Graham’s refusal to go to bat for Pauli Murray when she applied to grad school at UNC also comes to mind. And as Andy Thomason of the Chronicle of Higher Education pointed out in this thread, there are strong similarities to the denial of tenure to Sonja Haynes Stone in 1979.