AT THE START, UNC’s coal power plant was on campus for 45 years before being moved to its present location on the edge of downtown. Back when the power plant was operating so close to classrooms and dorms, a student wrote a poem about it in 1922 that ran in the Daily Tar Heel.

ODE: TO SMOKE

By Meade Feild

We’ve heard about fogs in London,

As thick as the blackest night.

We’ve heard of Saharah’s sandstorms,

That blot out creations sight;

But the tales we heard were told by a bird

Who never came out our way,

For the smoke that comes from the power plant domes,

Send chickens to roost all day.

We’ve read about Polar regions,

And marveled their customs queer,

Where twilight runs for six long months,

And the sun never gets real near;

But look my friends where that smokestack ends,

Relinquish your wonders all,

For the truth you’ll grant, that a big power plant,

Makes bright mid-day, night fall.

We’ve watched the destroyers smoke screen,

As it hugs the ocean swells,

And surely thought that so much stuff,

Belonged to the Seven Hells.

But now who will dare such sights to compare,

With the smoke screen down our way.

For the smoke that comes from the power plant domes,

Sends chickens to roost all day.

“Chickens coming home to roost,” for those unfamiliar, is an old-fashioned saying meaning bad past actions come back to haunt to you.

WE’RE GOING to get to the news first today, and then come back to the history. There are some timely items on the agenda in the next few days regarding UNC’s power plant, which has been burning coal for the last 81 years adjacent to where historically Black neighborhoods happen to be.

I don’t have to tell you that climate change is here and an imminent threat to our planet and every generation from now on. You know that. UNC knows that. We’re in emergency territory. Yet UNC keeps burning coal despite a promise that it would stop by 2020.

UNC is even in the midst of a lawsuit over the power plant, being sued for alleged repeated violations of the Clean Air Act. The lawsuit was filed in December 2019 by the Center for Biological Diversity and the Sierra Club. It’s now in the summary judgement phase and it seems probable the judge will rule without a trial after both sides submit briefs based on the facts. Those briefs and their responses are due this month.

Now that discovery has occurred, UNC’s prospects don’t appear promising, according to Perrin de Jong, the Center for Biological Diversity attorney spearheading the lawsuit who is also from Chapel Hill. I spoke with de Jong at length this week, and he told me that after combing through UNC’s own records, the plaintiffs have now identified 7,830 documented violations of the Clean Air Act since December 2014. I’m going to say that again. That’s 7,830 violations of the Clean Air Act.

You can read the original complaint filed in court against UNC. The plaintiffs are seeking damages between $37,500 and $45,268 per day per violation since November 2009. That’s potentially, well, a hell of a lot of money.

Even more immediately, UNC’s Air Permit is up for renewal right now. The Air Permit is the document that sets the parameters for the operation of the power plant under Title V of the Clean Air Act and controls how much pollution it can create. According to de Jong and other activists, the draft of the Air Permit up for approval is a doozy. It appears UNC is trying to sneak a grenade by the public.

The Air Permit goes through North Carolina’s Division of Air Quality, which is a part of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. Those agencies are part of the state government, just like UNC. The last time UNC’s Draft Air Permit was submitted for renewal, de Jong said there were also major issues that led to its failure. Those problems had to do with improper measuring techniques of air quality around the power plant and in the Black community.

This time, the new Draft Air Permit is missing the heat input limit, de Jong and others have noticed. The heat input figure has been deleted from the paragraph where a capacity for Boilers #6 and #7 had been stipulated before, at 323.17 million Btu per hour for each boiler. Otherwise the language in that part of Paragraph A in Section 2.1 on “Specific Limitations and Conditions” is identical to the existing Air Permit. That would mean no enforceable cap on the amount of coal UNC could burn would exist. Presumably that would provide quite a bit more room to dodge getting sued again. Further, the section of the Draft Air Permit that extensively lists all the changes made to the permit from its previous version does not mention the deletion of the heat input limit. It’s just gone.

UNC’s vice chancellor for institutional integrity & risk management, under whose responsibility the Air Permit falls, and the public information officer for North Carolina’s Division of Air Quality did not respond to interview requests.

There are some opportunities for action in the next couple of days. First will be a press conference Monday held by activists, including de Jong from the Center for Biological Diversity, and representatives of the Climate Reality Project of Orange County, the Sierra Club, Earth Uprising Chapel Hill, and the Chapel Hill Organization for Clean Energy.

PRESS CONFERENCE

Monday, May 3, Peace and Justice Plaza, 5 p.m.

People can also attend via Zoom by registering at this link

Further, the Division of Air Quality will hold a remote public hearing on UNC’s Draft Air Permit.

PUBLIC HEARING

Tuesday, May 4, remote, 6 p.m.

Link to attend and more details here and here

You can register to speak at the hearing until 4 p.m. Tuesday.

There is also a public comment period on UNC’s Draft Air Permit that ends this week.

PUBLIC COMMENT

Ends on Thursday, May 6, 6 p.m.

You can submit thoughts on the permit and UNC’s power plant to DAQ.publiccomments@ncdenr.gov with the subject line "UNC.15B" or leave a voicemail at (919) 707-8726. Folks with Climate Action NC (part of the League of Conservation Voters), the Sierra Club, and the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League have put together this Frequently Asked Questions document that includes suggested language. The Chapel Hill-Carrboro NAACP has also been circulating the FAQ document.

Last decade, UNC backed out of a pledge to end the burning of coal by 2020. It has reduced the amount of coal it burns and increased the plant’s reliance on natural gas instead. Last Sunday, an article in the New York Times explained that natural gas is also a major problem. It began: “A landmark United Nations report is expected to declare that reducing emissions of methane, the main component of natural gas, will need to play a far more vital role than previously thought in warding off the worst effects of climate change. The global methane assessment, compiled by an international team of scientists, reflects a growing recognition that the world needs to start reining in planet-warming emissions more rapidly, and that abating methane, a particularly potent greenhouse gas, will be critical in the short term.”

In April, UNC released its “Sustainable Carolina” climate change plan, the timing of which amid this lawsuit and the Draft Air Permit is interesting. Its new Climate Action Plan states that the “responsibility of being a leader in Climate Action has never been greater for Carolina” yet it still contains no goal for when to quit burning coal. Only that UNC is “committed to eliminating the use of coal as quickly as is technically and financially feasible.”

De Jong says that the plaintiffs’ suggestion from the start of the lawsuit has been that UNC, like everyone else, tie into the grid, where energy is coming from cleaner sources than UNC’s.

UNC contends that its power plant’s existence is necessary because UNC must produce its own electricity due the hospital and other sensitive operations in labs and other research. This logic presumes that it is necessary for all hospitals and all research institutions to run their own power plants rather than plugging into grids everyone else uses. This is, of course, not the case. There are ways of ensuring that electricity would be maintained in the event of a power outage. It’s also something to claim that coal must still be burned and the air must be polluted up the hill from a hospital that surely treats patients suffering from illnesses connected to the power plant.

And with that, let’s go to the archives to see what’s coming home to roost…

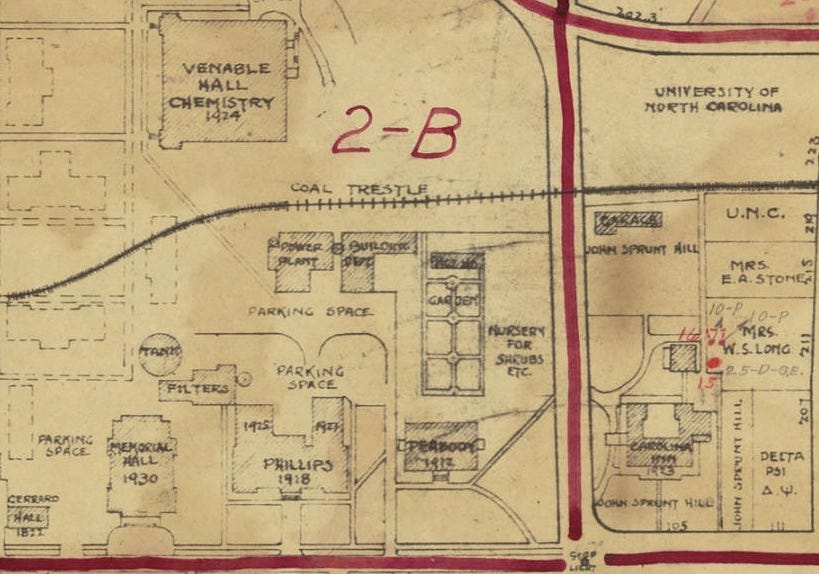

THE DIRTINESS of the coal power plant’s pollution is a story that far predates its move 81 years ago to its current location. In fact, it goes all the way back to 1895 when UNC first opened a power plant about where Phillips Hall is today. I did some digging this week in newspaper archives and in documents preserved in the University Archives to learn more.

For many decades, UNC supplied the campus with electricity and sold electricity to the entire town, the legal justifications for which got a little dicey when UNC built a new plant on the west end of Cameron Avenue in 1940 and financed part of the construction with revenue bonds backed by the “surplus” energy it would create and sell, and again when its franchise agreement for a public utility with the town was expiring in 1968.

The power plant grew and changed immensely in the first several decades of its existence as energy technology and needs developed and the university and town grew. The facility moved around a little but not much, operating in what would today be near the center of campus, until eventually being relocated off campus.

For decades, the power plant was across Columbia Street from the Carolina Inn about where Chapman Hall is today, behind Phillips Annex and Carroll Hall. Unsurprisingly, the power plant was not a beloved fixture on the campus. It was such an eyesore, among other things, that less than a year after the current plant opened, the editor of the Chapel Hill Weekly called the university to ask why in the world it hadn’t yet torn down the 150-foot-tall smoke stack still on campus.

Gripes and problems had persisted for decades. In 1936, some relief came to the ears of all when a Maxim silencer was installed on the exhaust line of the engine, ridding campus of the “steam engine’s chug-chug.” Back then, the railroad tracks that now frequently bring coal to the Cameron Avenue plant extended to campus and ended on a steep downhill slope. One day in 1931 when 10 train cars full of coal were being delivered, someone forgot to attach the last full car at the end to the other cars and it became a runaway with 44 tons of coal aboard. The car crashed through a barrier of railroad ties and dumped the coal all over a walkway in front of the library.

FIFTEEN YEARS after that poem in the Daily Tar Heel about the plant’s pollution, faculty members were sent a one-question survey asking to briefly state one thing UNC should do to improve. The DTH published some of those answers in 1937. W.F. McNeir stated: “Nothing better could be done than to clean up the hideous environs of the power plant and the chemistry building. Have you ever been through that part of our property? Go and look at it.”

The next year, UNC decided to move the power plant off campus. The Chapel Hill Weekly noted in a news article about the upcoming construction boom: “More important for the University, an unsightly conglomeration—boiler and engine houses, railroad tracks, out-buildings, rubbish—would be removed from campus, and four nuisances—smoke, cinders, ashes, and noise—would be ended.” A week later, a front-page editorial celebrated to decision. It stated that “no physical improvement in the history of the University has ever been so important” and that for years Chapel Hillians and visitors had “deplored the presence on the campus of the unsightly conglommeration [sic].”

In 1938, UNC began a major buildings boom with the help of federal government money after the Great Depression. Originally the plan was for the outdated campus power plant to either be rebuilt or renovated. That plan was submitted to the government for approval. But the Buildings and Grounds Committee, headed by William C. Coker, had an urgent idea they took to the administration, then led by Frank Porter Graham. If the university invested hundreds of thousands of dollars to upgrade the power plant, they’d be stuck with it on campus. If they were going to rebuild, they ought to expel the nuisance from campus. And so a new plan was submitted and the current power plant was built in a hurry. It opened in the summer of 1940.

By the time UNC decided to move the power plant, it was burning in excess of 21,000,000 pounds (10,500 tons) of coal per year. The amount had nearly tripled over the prior decade. Yet there’s not much evidence that concern for the people who would soon be living near the new power plant, situated next to Pine Knolls and Tin Top and other Black neighborhoods, was much of a consideration.

The only mention I came across from the planning phase was when an architect highly concerned with the aesthetics of the new facility (it should match the colonial buildings on campus) suggested that instead of an unsightly towering smoke stack, they should build three low stacks that would be housed inside the building. It was pointed out that doing so would create a number of problems that would need expensive troubleshooting. It was also pointed out in a memo that those “low stacks would also make a smoke nuisance in the vicinity of the plant and the University would probably have some suits on its hands unless this expensive soot remover equipment were installed and operated.” Frank Porter Graham wrote to go ahead with the low stacks plan, but evidently that was abandoned, likely due to feasibility, and a tall chimney was built.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after the new power plant took over energy production off campus, complaints rolled in. There doesn’t seem to have been coverage of it in the newspapers, but there are some references in the University Archives.

The new plant went into full operation about August 1940.

On November 12, 1940, a memo with the subject “Elimination of Soot and Smoke for the New Power Plant” went out. It argued that an expensive “soot eliminator” was not necessary because it was normal for a new plant to create an excess amount of noticeable pollution to its surroundings as it got running and kinks were worked out. The builder of the equipment reassured the university that generally the ash and soot would travel 20 to 30 miles.

In March of 1941, Frank Porter Graham asked for information on fly ash precipitators. It was reported back to him that only three fly ash precipitators were in use within 300 miles and that they did not eliminate all fly ash. It was also reported that the new, improved plant was saving UNC money on top of paying off the bond requirements.

Around May of 1941, a meeting of residents of the Westwood neighborhood and “others concerned” took place with university administrators in Gerrard Hall. Westwood was a white neighborhood just south of the power plant.

On June 10, 1941, in a memo to Graham on the subject of “Smoke and ash from the New Power Plant” it was reported: “There is no question but that any power plant, with or without ash and soot precipitators, will always be a nuisance to some degree. There is also no question but that residents of the vicinity are justified in their contention that part of the difficulty they are experiencing is due to the new plant.” It had been determined that one source of the problem might have been dust blowing from the coal and ash piles. The memo says that “residents of the section immediately south of the plant are justified to some degree in their feeling that the new plant is responsible for their difficulties.”

On June 14, 1941, Graham decided to go with the significantly less expensive version of the soot precipitators to alleviate “a most peculiar situation.”

AS AN EXAMPLE of how officials and decision-makers thought of local Black people during the time when the power plant was moved, a recurring issue at the time in Board of Aldermen meetings for the Town of Chapel Hill was “Negroes” who were “loafing” on Franklin Street in the business district. It was an agenda item at a 1938 Board of Aldermen meeting, and again in 1939.

In the September 29, 1938 minutes from the Board of Aldermen, an agenda item near the top reads:

Subject: Negroes loafing on the streets.

Upon motion by Alderman Bowman and seconded by Alderman Burch, the Board of Aldermen of the Town of Chapel Hill resolved that the Police Department should patrol Franklin and Columbia Streets every Saturday and if any negroes or white were found loafing, they should be arrested for vagrancy.

On June 14, 1949, an agenda item read:

Subject: Negroes on Franklin Street.

In order to relieve pedestrian traffic on Franklin Street on Saturdays, the Board of Aldermen agreed to place benches along the sidewalk on Columbia Street for negroes in order to take them off the sidewalk in front of the business district.

It’s no stretch to imagine that barely a thought would’ve been given to how a coal power plant’s pollution would impact the public health of its adjacent Black communities, neighborhoods full of people whose labor kept the university and town running for poverty wages.

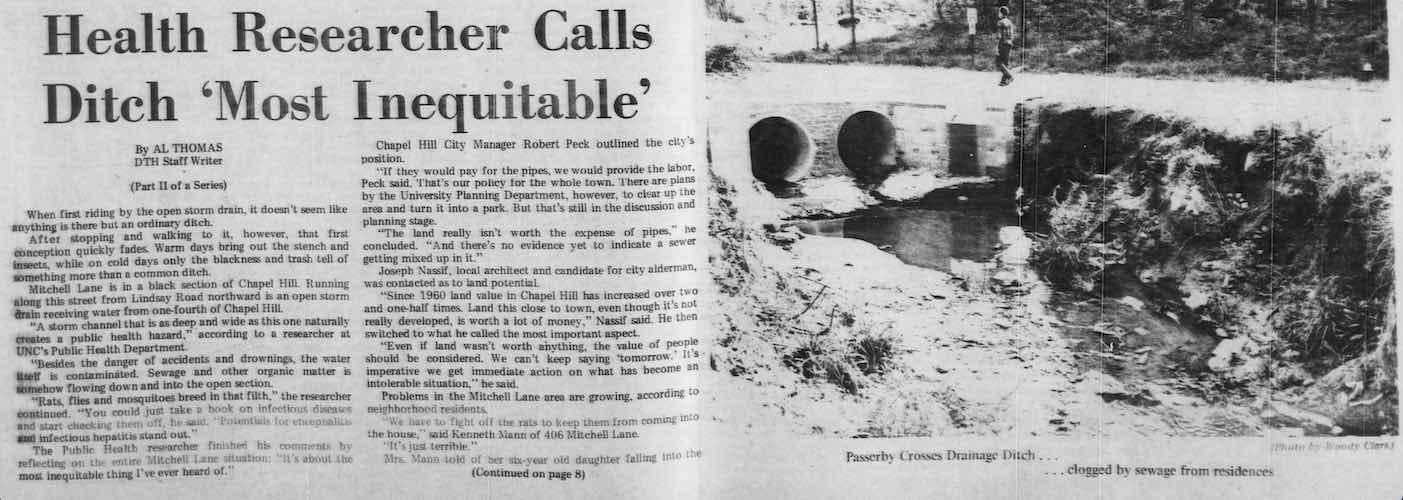

Neglect of this sort has long been a defining feature of this area’s relationship with those communities. Below is a DTH article from 1969, three decades after the power plant was moved, about a horrendous storm drain ditch in a downtown Black neighborhood. It details the stench, insects, trash, flowing sewage, rats, and mosquitos breeding there. A Public Health Department researcher is quoted saying: “You could take a book of infectious diseases and start checking them off.” It was fear of infectious diseases that could spread from there to the nearby white neighborhoods that belatedly got Black neighborhoods proper water and sewer systems.

You only have to go four miles north of the power plant to find another major example of environmental racism: the Orange County Landfill that required a 50-year-saga for local municipalities to make good on promises made to the Rogers-Eubanks community when the landfill was installed there, with no liner, in the 1970s for what was supposed to be just a short time.

Now despite having subjected neighbors to the coal power plant for generations, despite the effects of climate change that have already wrecked places in North Carolina, despite a promise, here is UNC still burning coal 126 years after it began doing so in 1895. All the while, UNC is fighting a lawsuit over allegedly violating pollution laws thousands of times and is quietly trying to erase the limit on how much coal it can burn going forward, in the year 2021, still trying to keep those chickens from coming home to roost.

ONE GOOD THING:

More than 100 million people are now fully vaccinated, about 40% of the adult population. Still a ways to go, but progress. Walk-in and pop-up vaccinations are becoming more of a thing.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

Lawsuit and Air Permit

Original complaint Case No. 1:19-cv-1179, UNC response, other court documents via PACER, North Carolina Division of Air Quality, UNC’s Sustainable Carolina Climate Action Plan

“Lawsuit against UNC claims coal plant could pose health risks to community”: Daily Tar Heel, January 7, 2020

“Judge denies UNC’s motion to dismiss allegations of violating Clean Air Act”: Daily Tar Heel, October 18, 2020

“Court Denies UNC’s Request to Dismiss Claims That University’s Power Plant Burned More Coal Than Permitted”: Center for Biological Diversity

Newspaper Archives

“New Power Plant Here: To Take Place of the Old Condemned One in Near Future”: Daily Tar Heel, March 18, 1916

“Extensive Building Program To Begin At An Early Date”: Daily Tar Heel, April 26, 1921

“ODE: TO SMOKE”: Daily Tar Heel, February 3, 1922

“Power Plant Is Now Thoroughly Modern”: Daily Tar Heel, February 21, 1925

“Large Crowd Is Attracted When Car Is Wrecked: Runaway Coal Car Jumps Railroad Track and Crashes Into Campus Walk”: Daily Tar Heel, December 2, 1931

“University Maintains Service Plants For Students’ And Townspeople’s Use”: Daily Tar Heel, May 6, 1932

“Steam Engine Chugs Quieted By Silencer”: Daily Tar Heel, November 1, 1936

“Profs Suggest Next Steps U. N. C. Should Take To Improve Itself”: Daily Tar Heel, April 20, 1937

“Relocation Of Power Plant To Be Considered”: Daily Tar Heel, May 18, 1938

“Power House away from Campus Part of Expansion Plan Which Is, So Far, in Realm of Hopes”: Chapel Hill Weekly, May 20, 1938

“Many New Buildings to Be Begun Here before Jan. 1 As Result of Governor’s Calling Special Session”: Chapel Hill Weekly, August 5, 1938

“If Govt. Gives Requested Aid, Construction to Total Cost of $1,649,000 Will Begin Soon”: Chapel Hill Weekly, September 9, 1938

“Building of Power Plant away from Campus Will Be of Great Importance to University”: Chapel Hill Weekly, September 16, 1938

“Dining Hall, Two Dorms Will Be Put Here By PWA: $700,000 Power Plant To Be Erected Near University Laundry”: Daily Tar Heel, September 16, 1938

“Administration Lets Contracts For Power Plant”: Daily Tar Heel, December 2, 1938

“Zoology Department Moves Into New $187,000 Building” Daily Tar Heel, March 30, 1940

Wilson Library Archives

University Archives:

Energy Services Department of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1934-2001

Board of Trustees Records, Series 1: Minutes

President Records, Frank Porter Graham: Subseries 2.2.4 Business & Finance

Vice Chancellor Business & Finance: Subseries 1.1, Subseries 2.9, Subseries 5.1

Officer of Director of Utilities

North Carolina Collection:

North Carolina Maps, University of North Carolina (1793-1962)

North Carolina Image Reference Cards, 1839-1990

Board of Aldermen Minutes, Town of Chapel Hill

1938-1940