Note: This edition of Stone Walls has two shorter items, followed by a new regular feature.

NARRATIVES get constructed over time by those with access to the tools. Choosing what to include, what to emphasize, and what to leave out all shape the story, as the “Southern Part of Heaven” so starkly illustrates. Narratives are often fundamental to how groups think of themselves and their places. But they’re also living things that continue changing shape, albeit gradually. That’s largely what Stone Walls is about … trying to penetrate popular narratives that obstruct a fuller picture.

Some smart people in a recent Zoom meeting brought up narratives in the context of how much of the local history work being done by many these days is with the purpose of dismantling narratives that stand in the way of progress. Chapel Hill’s narratives are so imbedded they often have to be deconstructed before enough people can see a necessity for change. That obstacle adds a degree of difficulty.

Thankfully, many are working to chip away. There are activists and organizers, archivists and librarians, teachers and students, neighbors and relatives, historians and community storytellers, researchers and writers, and every person who passes on a fact to someone else. I’m thankful for you all. Stone by stone, we unlearn some of what we thought we knew. In doing so, we make space for more truth.

It’s a longterm project, but some evidence worth noting of narrative shift has been appearing more frequently of late. Most recently, Carrboro, which has been under pressure to alter its name or namesake, just renamed the neighborhood Plantation Acres and is looking at doing the same to Phipps Street, which I wrote about in 2018. Significantly, much of that initiative is coming from the people.

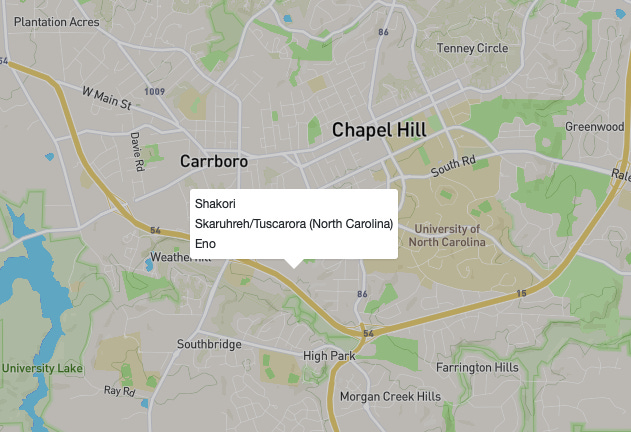

Then came this past Monday, which was University Day, Columbus Day, and Indigenous Peoples’ Day. A campus petition asked UNC to recognize the annual Indigenous Peoples’ Day — as Chapel Hill, Carrboro, and North Carolina’s governor already do — but the chancellor declined. Again, narratives take time. And I encourage you to check out this world map showing where Native lands were, and to read this article about stolen Indigenous land keeping UNC financially afloat.

As for University Day though, there was a more positive development in that powerful piece of the local narrative. University Day marks UNC’s birthday as the anniversary of the laying of the cornerstone for the first building of the first public university in the nation. The elaborate cornerstone ceremony conducted by UNC’s founders in 1793 has long been celebrated and replicated. There’s even a mural in the downtown post office depicting it.

The moment in history has always been told as one of great white men symbolically giving birth to the university by physically placing the cornerstone into perfect position. Of course, mural aside, it made little sense that no Black people would’ve been present, given how essential enslaved people were to the lives of the founders. But it turns out, not only is it likely that enslaved people were there, they might have been integral to the very moment we still celebrate 227 years later.

Masonic apron worn by William McCauley at the 1793 cornerstone ceremony

There is one account, that I’m aware of, that includes the story of an enslaved man named Dave placing the cornerstone instead. It also depicts a bit of incompetence by those grand white men. From the April 1990 issue of the University Alumni Report:

A legend of the McCauley family is that the Post Office mural is incorrect in two respects. First, General [William R.] Davie should have been wearing a hat. (Masons will understand why.) Second, the stone was not lowered into place by a hoist and windlass. The family says that the stone was heavier than anticipated, and the hoist rope broke. When this occurred, [Matthew] “Bung” McCauley, a small man, turned to Big Dave, his body servant, a 6’5” slave who weighed 300 pounds, and said, “Dave, pick it up and put it in place.” The story is that Dave put his arms around the stone and lifted it onto the spot designated by General Davie.

It’s something to imagine that this moment was punctuated with the words: “Pick it up and put it in place.” It’s even more intriguing to know that not only did enslaved people physically construct UNC’s early buildings, but Dave might actually have been the person who laid the first cornerstone of such lore. It would be fitting.

The article was co-written by Kemp Battle Nye, who was a McCauley descendant. I first came across the anecdote last year while researching the lynching of Manly McCauley. At least one of Manly’s parents likely had been enslaved by one of Matthew McCauley’s sons. Bill Burlingame’s research for the Chapel Hill Historical Society on the McCauley family cemetery, which UNC maintains by University Lake, cited the article.

On University Day, the University Archives account tweeted about Dave and the article. Then the rope holding the 227-year-old narrative frayed a bit when UNC’s official communications arm published a piece about Dave and the cornerstone the next day. A pretty good one. And the official UNC Twitter and Facebook accounts shared it. There’s still a long way to go. It’ll take time. But narratives are shifting.

For additional background on University Day’s roots, check out this Twitter thread.

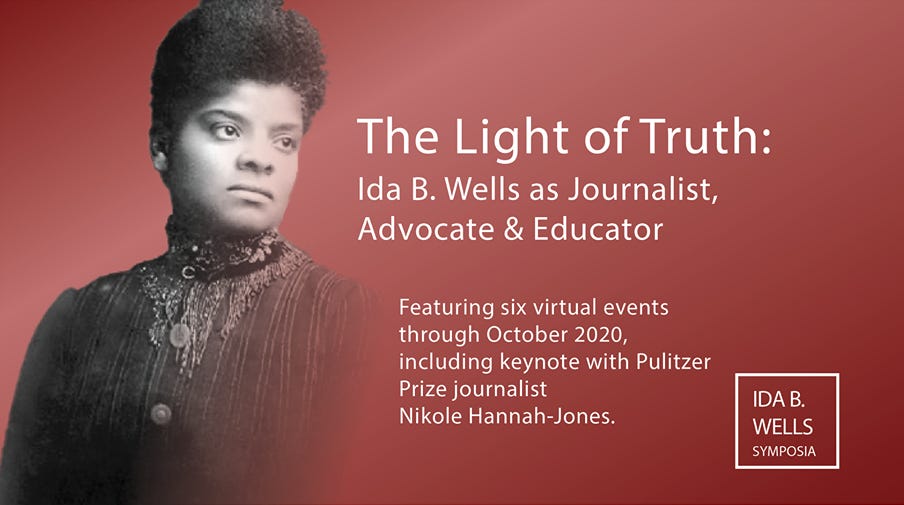

THROUGHOUT OCTOBER a series of virtual events are being held as part of an Ida B. Wells symposia, hosted by UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South and the Orange County Community Remembrance Coalition. (I am a member of OCCRC but was not involved in planning the symposia.)

The opening event featured Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ron Nixon, and Topher Sanders — founders of the Ida B. Wells Society For Investigative Reporting, now housed at UNC’s journalism school. I want to highlight something Hannah-Jones said during the discussion. In case you don’t know, Hannah-Jones is a Pulitzer-winning journalist for the New York Times Magazine, and speaking of breaking down founding narratives by reframing history, she created the 1619 Project. She is also a UNC alum.

A question came from my friend Danita Mason-Hogans, who sits on UNC’s Commission for History, Race, and a Way Forward (the commission formerly known as History, Race, and Reckoning) and is also in OCCRC. She asked what part universities like UNC should play in addressing harms their historical injustices, including pushing white supremacist narratives, continue to have on local Black communities. For example, the Chapel Hill-Carrboro public school system has one of the worst racial achievement gaps in the nation.

Hannah-Jones responded:

I've been very vocal about this. I think public universities, universities in general, play a tremendous role in both creating the inequality, sustaining the inequality. And I think that they also are often one of the most powerful institutions in the communities they serve. They employ the large number of people, and they wield a tremendous amount of power around how the rest of the town, especially in a college town like Chapel Hill, operates. And yet they've largely thrown their hands up on using that influence to bring about more equality. Which is not surprising because they also tend to operate with a lot of inequality on the campuses.

So a place like UNC — which literally is a university founded by enslavers, many buildings dedicated to enslavers, enslaved people lived and worked on the campus — and yet as far as we seem to ever want to go is to study the issue. And it is time for more than study. There is time for restitution.

I've advocated that I think that universities like the University of North Carolina should actually implement scholarships for descendants of American slavery. Particularly, those descendants should be able to attend universities at either a very deep discount or free. I think that you have to be serious that restitution has to come in more than just thinking and contemplating what was done, but actually trying to address the harm. I don't think you should be expecting people to go into buildings named after people who operated forced labor slave camps. So I think, yeah, clearly this a university that is willing to pay a lot of money to preserve monuments to white supremacist enslavers. It would be good to see that same effort being put towards addressing the harms of those white supremacist enslavers.

Hannah-Jones then reflected on an observation she’s made while staying at the Carolina Inn: The alumni featured in photographs on the wall, another form of narrative building, are almost all white due to UNC’s history of exclusion. “There are Black people in Chapel Hill right now who were denied entry, who were not able to attend a university that was their state university that their parents and they paid tax dollars for. You could find living victims to pay restitution to if you wanted. This is not an ancient legacy. And we need to be clear about that ongoing legacy with living victims right now.”

The full event is viewable here. The question came at the 55:30 mark.

ONE GOOD THING:

I’m trying out a regular item called “One Good Thing” because we all need some bright spots these days. The first is a quick scene:

The house across the street from me was built by a formerly enslaved man. It wasn’t as long ago as you might think either — in the 1930s — and six generations of his family have lived in this home now at one time or another. This year the house got a renovation for more generations to enjoy. A few evenings ago, as the job was wrapping up, I happened to look out my front window. The contractor who did the renovation is a retired NFL player, and he was out in the yard throwing a football with a member of that sixth generation, a young boy. Tossing the ball back and forth. Teaching. Having a catch. It was like seeing the final scene of “Field of Dreams” come to life.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

“‘That’s not where we want to go.’ Carrboro drops neighborhood’s Plantation Acres name”: News & Observer

“Carolina Indian Circle fights for University recognition of Indigenous Peoples Day”: Daily Tar Heel

“Without profit from stolen Indigenous lands, UNC would have gone broke 100 years ago” by Lucas P. Kelley and Garrett W. Wright: Scalawag

“What Happened To Old East Cornerstone”: The University Alumni Report, April 1990

“Re-examining Old East”: The Well

“Manly McCauley” by Mike Ogle: OCCRC

The Light of Truth, symposia on Ida B. Wells: Center for the Study of the American South

“The College-Town Achievement Gap”: The Atlantic

Map: Native Land

Photo of William McCauley’s Masonic apron: North Carolina Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Black-and-white sketch of cornerstone ceremony: The University Alumni Report, April 1990

Photos of mural and cornerstone: Mike Ogle