A COUPLE of newsletters ago, in “Police Problems,” Stone Walls promised a followup with some historical incidents and facts relevant to local law enforcement. Below you’ll find that incredibly incomplete list. It’s not difficult to see reflections of the past in the events of today. The present doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

There’s also a parallel between what has bolstered the Black Lives Matter era and strengthened the civil rights movement at the intersection of violence and technology. The mid-20th century civil rights movement got a dramatic boost from the emergence of home televisions. News broadcasts brought to life the horrific treatment Black citizens faced, often at the hands of police. In recent years, camera phones put that power directly into the hands of citizens. It’s unfortunate that so many white people require video evidence of violence and abuse to believe. But it is reality.

Nikole Hannah-Jones — Pulitzer Prize winner, 1619 Project creator, and UNC alum — pointed out in this thread that in the 1960s it was violence (specifically, violence caught on camera) that made the difference, rather than the doctrine of nonviolence, as many tend to think. And as is the case again.

The vast majority of the history of policing did not have cameras pointed at it though. So let’s take a look at some of that local history. As we do, consider how it connects to the way law enforcement and criminal justice operate today. And how it connects to distrust in the system.

A common refrain about police misconduct is that “bad apples” explain away harmful and violent behaviors as acts simply of individuals with ill intent (or incompetence). A lot of bad apples apparently. Bad apples empowered with the weight of the law and the finality of lethal force. Bad apples who rarely face meaningful consequences. The “bad apples” argument also doesn’t address the clear systemic issues forever at play, nor that the problems extend to prosecutors and judges who wield tremendous power — life-and-death power — as well.

This is not intended to be a comprehensive list. Far from it.

Policing in the American South, Chapel Hill included, has its roots in slave patrols — groups of white men organized to catch runaway enslaved persons, to guard against insurrections, and to generally protect the system of slavery as its economic foundation. “ … the first formal slave patrol had been created in the Carolina colonies in 1704 … during Reconstruction, many local sheriffs functioned in a way analogous to the earlier slave patrols, enforcing segregation and the disenfranchisement of freed slaves.”

Of Chapel Hill during slavery, Kemp Plummer Battle wrote in History of the University of North Carolina, Volume 1: “All white males between 21 and 50 years of age were distributed into classes and in turn patrolled the streets at night. Slaves were liable to a whipping of ten lashes, or a fine of one dollar, for being absent from home without a written permit from the owner.” Free Black people in many parts of North Carolina had to wear a cloth patch that read “FREE” on their left shoulders.

On the streets, Black people were also prohibited from preaching, having an unlicensed gun, and buying or selling liquor. From A History of African Americans in North Carolina: “State courts also granted wide ‘discretion’ to the often violent patrollers, instructing juries not to ‘examine with the most scrupulous exactness into the size of the instrument, or the force with which it was used’ against a slave unlucky enough to fall into the patrol’s hands.”

According to Battle, when a local man named Tom was sold to a slave trader, he ran away and lived in a cave in the woods. A posse eventually located him, scared him out, and shot Tom in the legs. Then he was sold into the deep South. The condition of his cave was described as beastly and became a source of laughs for generations of white Chapel Hillians passing down the story.

When an enslaved man named Asgill was hanged for killing another enslaved person, UNC students gleefully brought Asgill’s body back into town. They placed his head in a bag and forced another enslaved person to deliver it to a store clerk as a prank.

Following the Civil War when Union forces banned whipping in North Carolina, UNC’s president, David L. Swain, and two trustees visited President Andrew Johnson to try to persuade him to lift the order.

The bragging story that Julian Carr told at the dedication of the campus Confederate Monument of his horsewhipping a “negro wench” in town after the war was an expression of that slave patrol mindset to maintain social control. He was re-emphasizing that ethos a half-century later, in 1913.

In 1870, amid sustained Ku Klux Klan terrorism in the area, conservatives staged a nonviolent coup of Chapel Hill’s government with a phony election that ousted its rightful officials. The objectionable officials included a Black constable, a Black justice of the peace, and two Black town commissioners. The illegitimate new government was undone after five weeks.

In the 1880s, chain gangs built the 10-mile railroad connector for UNC. During construction, guards whipped to death Andrew Fries, a Black prisoner. Reports leaked of regular beatings, and UNC’s president, Kemp Plummer Battle, acted to cover up the brutality and smooth over the school’s culpability in the murder. A judge who’d been a leader of the county KKK dismissed the case.

UNC students were known to torment local Black people for kicks, and in 1886 James Weaver was “cruelly whipped” on campus by some who also threatened to whip his friend Pat Brewer. A week later, following an argument, armed students marched into the Black community late at night. During the confrontation, one student was killed and another was wounded. Brewer was sentenced to 10 years. A student evaded charges for the whipping with UNC’s help.

Manly McCauley, 18, was lynched in 1898 just outside of Chapel Hill by a posse that hunted him after he and the wife of a white farmer ran off together. Four men were eventually arrested when McCauley’s uncle pressed the issue. One of the four was acting as an officer of the law, according to one report. They were immediately acquitted. During the same decade, another Black man was repeatedly pursued by posses, even shot and thought to have been lynched, for alleged overtures toward white women. He went to prison.

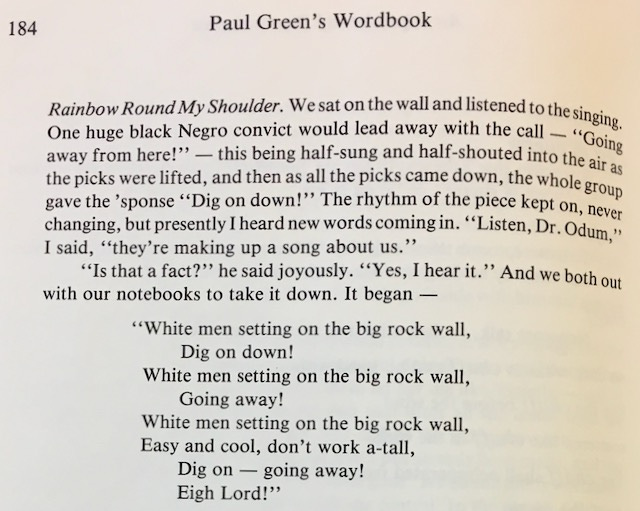

Around 1920, Franklin Street got paved for the first time, using chain-gang labor. Years later, a popular newspaper columnist fondly recalled the spectacle as boyhood entertainment: “We’d watch with awe as manacled and beautifully singing prisoners, six abreast and with picks flashing in the hot, dusty sunlight, hand-graded the new paved road.” Paul Green also wrote of the scene, which he took in with another local, liberal leader of the era. (Green later wrote a play, “Hymn to the Rising Sun,” about the abuses of chain gangs.) Green said the prisoners paving Franklin put him into their lyrics:

A race riot erupted in 1937 where the downtowns of Chapel Hill and Carrboro meet that culminated when a gang of white men on the back of a flatbed truck with railroad ties affixed to its front roared from the Carrboro fire station toward the Black residents. They shot rifles and pistols into the crowd while driving through, the Black people returned fire, and then the truck turned around for another pass. More than a hundred shots were fired. Earned mistrust in local police by the Black community had helped spark the shootout. Afterward, Chapel Hill, Carrboro, and UNC joined purses to secure for the police a Tommy gun, grenades, and billy clubs with tear gas capabilities.

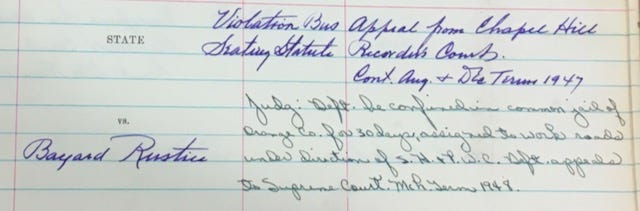

The 1947 Journey or Reconciliation, also known as the First Freedom Ride, came through Chapel Hill when activists tested a Supreme Court decision outlawing segregated seating for interstate travel. The only violence the group encountered was in Chapel Hill when the riders were attacked and followed by white taxi drivers. The riders were arrested though, for violating segregation law. A prominent local judge prosecuted the Freedom Riders as a private attorney, passionately defending Jim Crow in court as he described Black people as savages and rapists. The Freedom Riders were found guilty, and Bayard Rustin wrote about his resulting time on the chain gang.

Early Black police officers in mid-20th century Chapel Hill were hired to patrol Black neighborhoods, were assigned menial tasks at the station, and weren’t permitted to arrest white people.

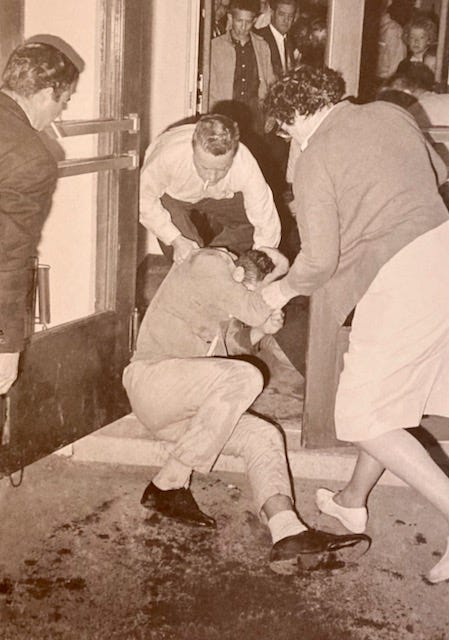

During the local civil rights movement of the early 1960s, nearly 2,000 arrests were made. When demonstrators were arrested for a sit-in at the Merchants Association, the chief prosecutor, who later became a Superior Court judge, refused to drop the charges despite recommendations to do so by the Merchants Association, mayor, police chief, and others. The Chapel Hill police chief, regarded as a thoughtful man, tasked all his officers with spying on the activists by cultivating informants and to “make lists of license numbers of cars seen around integrationist meetings,” according to The Free Men. When one restaurant’s owners beat a UNC professor/demonstrator so badly with a broom and kicks to the head that he blacked out twice, the police arrested the professor but not his assailants. A brain aneurysm killed the professor months later; whether it resulted from the beating was uncertain. Protestors also alleged beatings by police back at headquarters.

[Photo by Jim Wallace from a demonstration at Watts Restaurant, where a professor was beaten. Courage in the Moment]

When a Black UNC graduate student signed up his son for little league baseball in 1962, a league commissioner told a coach to resign for saying the boy should be allowed to play. The league dissolved rather than allow the boy to play. That little league commissioner was a prosecutor.

In 1970, when white supremacists stabbed James Cates Jr. on UNC’s campus, UNC and Chapel Hill officers let Cates bleed for an egregiously long time before taking him to the hospital, where he soon died. Police let the assailants flee, recovering no murder weapon or blood evidence from them, and UNC’s security officer and other employees immediately cleaned the blood from the crime scene. An all-white jury found the three men charged not-guilty following a perfunctory prosecution. When firebombings occurred after the verdict that injured nobody, more than a dozen young Black men and boys were arrested. Some went to prison.

Talk with Black local residents, or read and listen to oral histories, and it’s routine to hear accounts of the police’s role in keeping Black people in their place, as police perceived it. Into the 1970s, Chapel Hill police were known for routinely attempting to keep Black people out of the white side of downtown after dark, acting like shepherds to nudge them back to their part of town. Police were also known to intimidate children for no reason other than emphasizing to them their place. They harassed Black men who ventured onto campus for purposes other than work, questioning them for thefts and assaults, or even beating them for talking to white women.

Beginning in the 1970s, the first Black female officer employed by UNC police started filing grievances complaining of racial and gender discrimination. She was far from alone, and eventually sued in 1990. She won, but UNC appealed twice over a judge’s “and/or” word choice mistake during jury instructions and won a new trial. While that re-trial was in court in 1995, the parties settled after battling for a decade and a half. During the ordeal, UNC’s police chief and an administrator overseeing the department were pushed out.

A drug raid in 1990 by Chapel Hill and Carrboro police in the Black business district resulted in a lawsuit for violating the constitutional rights of 37 people. Forty-five officers participated, including from Orange County and the S.B.I. Nobody on the block of Graham Street was allowed to leave without being checked by police. The blanket search warrant gave officers the latitude to search and arrest anyone congregating along the block where the Midway Business Center, Beer Study, and the Baxter are today. The district attorney declined to prosecute those arrested during the procedure because of the illegality of the raid in which police frisked everyone in a bar and on the street, and searched a house.

Another militaristic raid occurred in 2011 when Chapel Hill police sent a tactical unit with assault weapons to storm “anarchist” squatters in the Yates building on West Franklin Street without warning. Police reportedly pointed rifles at their faces and handcuffed two reporters. The legal result from such a dangerous flex of force was misdemeanor breaking and entering charges against seven squatters.

Numerous incidents surrounding protests, antiracist activists, and neo-Confederates related to the Confederate monument in recent years, both before and after Silent Sam came down. The undercover spying on students, apparent lying under oath, prosecuting charges with little to no chance of sticking, barring students from parts of campus, bicycles as weapons, smoke bombs, pepper spray, snipers on roofs, escorts and protection for white supremacists, confiscating canned goods collected by antiracists, knocking over an antiracist potluck table, arrest and termination of UNC’s assistance coordinator for student veterans who supported the campus antiracist movement, handshakes for armed white supremacists who’d threatened violence on students…

… UNC’s police chief retired during that period. Also, the night Silent Sam fell, an officer with the Chapel Hill Police Department guarding the statue was photographed with his tattoo representing a far-right, anti-government militia. Chapel Hill PD already knew about the tattoo. When caught, the department said he’d start covering the tattoo while on the job. Under further pressure, the officer was placed on paid leave and he finally resigned more than seven months later.

Are today’s “bad apples” disconnected from those of yesterday? Or is it the tree?

SOURCES & CREDITS:

Evolution of American policing: Time

“Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960,” by John K. (Yonni) Chapman

History of the University of North Carolina, Volume 1 by Kemp Plummer Battle

A History of African Americans in North Carolina by Jeffrey J. Crow, Paul D. Escott, and Flora J. Hatley Wadelington

Images of America: Chapel Hill by James Vickers

Chapel Hill 200 Years: “Close to Magic” by the Chapel Hill Bicentennial Commission, Town of Chapel Hill

“Manly McCauley, 1880-1898: Background on His Life in Orange County, North Carolina, and His Death by Lynch Mob just West of Chapel Hill” by Mike Ogle: occrcoalition.org

Bill Prouty’s Chapel Hill by William W. Prouty

Paul Green’s Wordbook: An Alphabet of Reminiscence, Volume I by Paul Green

“Race Riot” by Matt Robinson: indyweek.com

“Martin Luther King Jr. in Jim Crow Chapel Hill” by Mike Ogle: newsobserver.com

“Not So Deep Are the Roots” by James Peck, The Crisis magazine, September 1947

“We Challenged Jim Crow! A Report on the Journey of Reconciliation April 9-23, 1947” by George Houser and Bayard Rustin

Freedom Ride by James Peck

Orange County Superior Court Criminal Docket Book, March 1948 Term, photographed at the State Archives of North Carolina in Raleigh: Mike Ogle

The Free Men by John Ehle

“Second Generation: Black Youth and the Origins of the Civil Rights Movement in Chapel Hill, N.C., 1937-1963,” John K. (Yonni) Chapman’s master’s thesis

Courage in the Moment: The Civil Rights Struggle, 1961-1964 by Jim Wallace and Paul Dickson

Game Changers: Dean Smith, Charlie Scott, and the Era that Transformed a Southern College Town by Art Chansky

Background on James Cates by Mike Ogle: threadreaderapp.com

On the campus police discrimination lawsuit: numerous newspaper articles and documents from the University Archives

“North Graham Street search results in 13 arrests, crack seizure”: Daily Tar Heel, Nov. 19, 1990

“Police raid street block, arrest 13 in Chapel Hill”: News & Record, Nov. 18, 1990

“Lawsuit alleges Graham Street drug raid violated Constitution”: Daily Tar Heel, Sept. 12, 1991

“Chapel Hill Police Violently Arrest Squatters at Yates (University Chrysler) Building”: orangepolitics.org

“Yates building raid to be further investigated”: dailytarheel.com

“Chapel Hill: cops vs. anarchists and no one wins”: indyweek.com

“Violence at Silent Sam? UNC invokes risk in defending use of undercover cop.”: heraldsun.com

“A UNC Police officer has been accused of lying under oath in a Silent Sam arrest case”: dailytarheel.com

“Police pepper spray protestors”: youtube.com (News & Observer)

“Eight arrested at latest 'Silent Sam' protest on UNC campus”: wral.com

“Confederate group brings guns to campus; no arrests made”: dailytarheel.com

“Officer’s tattoo causes chief to ‘question his ability to function effectively’”: charlotteobserver.com

“Chapel Hill Police Officer with 3 Percenter Tattoo Resigns”: chapelboro.com

Photo of bloodied protestor at Watts Restaurant: Jim Wallace, from Courage in the Moment: The Civil Rights Struggle, 1961-1964

Photo of Yates building raid: Originated from the News & Observer, widely circulated without attribution

Photo of blue smoke bomb: News & Observer