This Saturday, November 21st, is the 50th anniversary of James Cates Jr.’s murder at the age of 22. Mr. Cates, a lifelong Chapel Hillian, was stabbed on UNC’s campus in 1970, and a significant delay by police in getting him to the hospital proved fatal. Two years ago, I published some research on the circumstances of his death. The “Re/Collecting Chapel Hill” podcast also examined the tragedy, calling James Cates the Emmett Till of Chapel Hill. Their episode includes audio from a talk I gave with Minister Robert Campbell in 2019 for the Center for the Study of the American South, as well as interviews with and analysis from people more closely connected to events than me.

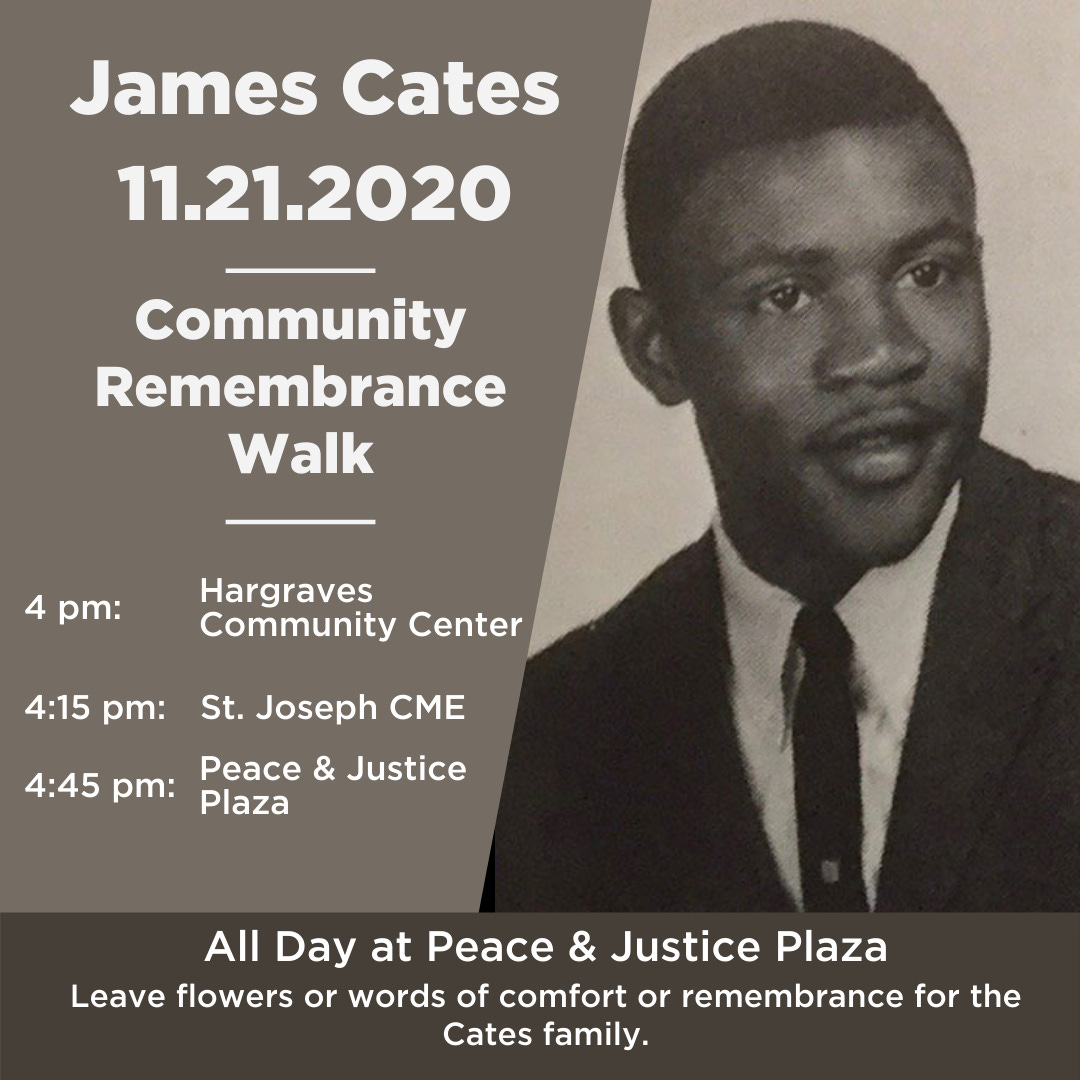

There will be a JAMES CATES COMMUNITY REMEMBRANCE WALK on Saturday beginning promptly at 4 p.m. outside Hargraves Community Center. More details are in the graphic at the end of this post. COVID is of serious concern, and all participants should wear a mask and maintain social distance. As an alternative to the walk, a table will be at Peace and Justice Plaza all day where people can leave flowers or notes for the family.

The following narrative — on James Cates’s life, his friendships, and his community’s loss — is published here with the consent of family representatives Nate Davis, retired director of the Hargraves Community Center, and Valerie Foushee, North Carolina state senator. Both are first cousins to James Cates Jr.

JAMES LEWIS CATES JR. lived a life with certain boundaries. That’s the way things were. It’s how life was for those in his home, the house next door, up the street, and on every block in their one-third of a square mile in downtown Chapel Hill. It’s how life was for neighborhoods similar to theirs across America.

Formerly enslaved people and their descendants began settling there generations ago, many in search of a life beyond work in the fields. James could draw an immediate line into that past through the grandmother, Annie Fearrington Cates, who raised him on Graham Street and with whom he lived until his death. Ms. Annie Cates’s father had been born during slavery, and she’d worked a tobacco field as a girl just south of town in Baldwin Township, next to what is today Fearrington Village, before moving away. Their neighborhood in Chapel Hill was comprised of a couple of pockets — Pottersfield and Sunset — that collectively became known as Northside. Northside made up the northwest rectangle of downtown Chapel Hill and overlapped into Carrboro. The people of Northside, plus the nearby neighborhoods of Tin Top and Pine Knolls, were united by forces and ancestors. But they were also bound by an unofficial set of rules they all knew best to abide.

Decades later, the Black Lives Matter movement would bring to light for the masses the fact of life that Black families had long educated their children on how to interact with police as a survival skill. But the rules passed on in their communities went well beyond. For example, people of Northside knew to be deferential to white folks in words and actions, to get out of their way on sidewalks, to speak when spoken to, and to address them with proper honorifics. They also knew they were expected to head back to Northside when done mopping floors, cooking dinners, building walls, and doing laundry, as Annie Cates did, for the community that surrounded them. It had been so for generations.

They knew, too, that once the sun was down, it was unwise to go past the railroad tracks west into Carrboro for risk of getting jumped by white, blue-collar guys in the old mill town. It was also safer not to venture east too far into white-collar Chapel Hill, where police often did segregation’s work well beyond the years when laws officially could. If Northsiders grew bold enough at night to push the boundary on foot, a police car was likely to ride up alongside, creep by, then circle and make more passes if necessary, until they took the message and turned back.

While white parents were telling their kids the sky was their limit, Black parents were telling their children not to wander too far east or west. The rest of Chapel Hill, and the bounties it had to offer, were not intended for them.

Even after James’s days, local Black people also knew that, aside from while laboring and for the few allowed to attend UNC as students, campus was risky territory. You might get hassled by cops and asked where you were headed. If there’d been some petty dormitory thefts, you were liable to get picked up for questioning. If you were a young man talking with a white woman, you might get the police called on you, even assaulted. You were not welcome, and that boundary was plain.

Still, there was joy in Northside. Joy was essential. And James Cates found an abundance with his friends. Growing up, his neighbors used each other’s homes like libraries, borrowing records and comic books at will, the Lone Ranger and Superman and Blackhawk, because “the library really wasn’t on our turf,” one of his friends told me. They’d listen to music and debate their favorite superheroes. Like many of his day, James dug Motown and soul. He had a soft spot for Otis Redding, who died when James was 19 when his plane fell from the sky. They’d play baseball or chat up girls at the neighborhood recreation center, originally named the Negro Community Center. When they got a little older, they’d carry on their lively conversations over hands of Tonk. James was tough at the card table, pool and ping-pong too, and reminded his pals with playful boasts as he collected their friendly wagers. Meanwhile in the background was an ever-present tension. James was born in 1948, and during their adolescence his age group saw their older brothers and sisters at the forefront of that collision as the civil rights movement came to Chapel Hill’s lunch counters and streets.

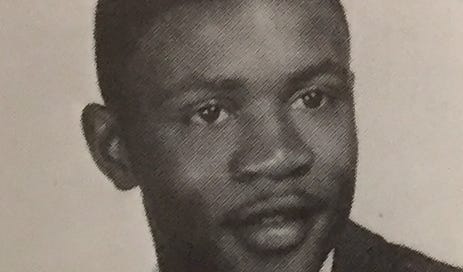

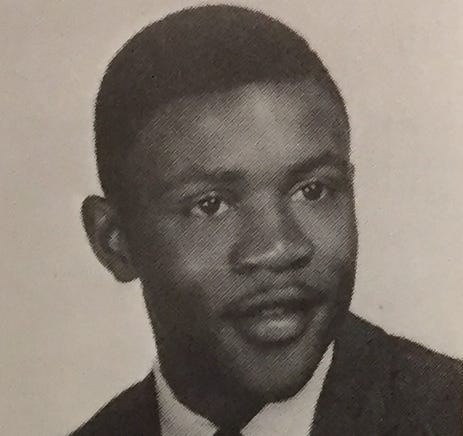

THEY CALLED him “Baby Boy.” Many friends and family members still do, even on first reference, 50 years later. Baby Boy was a small guy — perhaps not five-and-a-half feet tall — with cheeks to match his nickname. Yet armed with the potency of his personality, he was known as a bit of a ladies’ man. He was a smooth talker, clever and quick-witted. He was also a sharp dresser — button-down, tucked-in shirts and slacks, always pressed — and with a little cash in the pockets, his grandmother made sure. For many years, she labored at UNC, ironing at the University Laundry alongside many of her neighbors for discriminatory wages in a Jim Crow workplace.

“In his own way, [James] would be what you would call ‘The Fonz,’” Robert Campbell, a lifelong friend from Graham Street, told me in 2016, 46 years after he’d last seen James. James and Robert had both been in the Chapel Hill High School class of 1967. Their senior year was their first in that school because it was the first year it was fully integrated and the Black high school was closed. At segregated Lincoln High, James had been in student government and on the staff of the school newspaper, Echo. As Robert and I sat and talked, a woman joined our conversation who had been a school-age flame of James’s. She and James had connected in the days when they only needed five digits to call up somebody, and she recited by heart the number she’d given Baby Boy back when they were about junior-high age. Many nights he’d dial 9-9227 and the two of them would talk and talk until James fell asleep on the line. When Robert pegged James as their Black Fonz, she concurred with laughter. “Because if you wanted to know something, you go to Baby Boy,” Robert said and smacked the table. “He’d let you know if you got your tie tied wrong.”

Raney Norwood was another James pal from childhood on. As boys, they’d sometimes cut school and hide in Northside inside a section of concrete pipe, yakking and munching on sack lunches. As teens, their group of buddies would occasionally “borrow” the rec center bus on a weekend night, pile in, and ride to Durham to hear music and dance at The Stallion Club, where James could charm strangers into buying them beers. Raney spoke of his long-gone friend with a warmth that conveyed a sort of present-ness, almost as if the two of them, now aging men, could’ve had coffee together just that morning. “A real cool cat,” Raney explained to me, using “cool” to describe Baby Boy ten times during our 45-minute conversation. When our talk concluded and I was about to walk out the door, Raney had one more thing to say of James. “If he was living and you met him,” Raney said, “you’d walk away saying to yourself, ‘He’s my friend.’”

One Friday night when they didn’t get away to The Stallion Club, the weekend before Thanksgiving in 1970, there were two dances in Chapel Hill. The first was at what had been renamed the Roberson Street Community Center, and is now called Hargraves, in Northside. As a boy, James had played baseball on the field outside, unraveling unhittable curveballs from his short arms. The second dance would be a late affair at the heart of UNC’s campus, in the Student Union. Northside youth hit the dance at the neighborhood rec center, and after it ended James and his friends passed time in the Black business district on their end of downtown.

The second dance didn’t start until midnight at UNC. The Union and a campus Afro-American organization had partnered to sponsor an all-night dance marathon featuring two live bands until 7 a.m. One of the bands was a Motown-sound group out of Durham popular with Northsiders. The other was a rock group. The dance was to be purposefully interracial, the idea being to engender more positive race relations. That semester, of the 11,688 undergraduates enrolled full-time at the university, 240 were “Negro” (2.05%). Any successful interracial function on campus would need nonstudents to attend. Publicity and word-of-mouth had swirled through Northside behind the sails of the Durham band, The Dorvells.

When it came time to go, James and his friends were gathered outside of M&N Grill on Rosemary Street, at the end of James’s block of Graham, preparing to walk to campus. They spotted Robert Campbell, James’s friend from Graham Street, and stopped to chat. Robert had joined the U.S. Navy after Job Corps and was serving in the war, but that November he’d come home on R&R from Vietnam, where he patrolled rivers on a Mike boat. His ship was nicknamed “The Sample” for its model conduct on recovery missions rescuing fellow Americans from hostile territory. Now Robert was home for a short time to rest and recharge among loved ones in their one-third of a square mile.

James begged his buddy to go with them to campus for The Dorvells, to come along and extend their joy. But Robert was exhausted. James persisted, as he would, trying to smooth talk Robert out of calling it a night. James had a “gift for gab” and could talk himself into and out of most any situation. But Robert’s own bed and own pillow in his own house just up the block outweighed for Robert whatever further good times might lie ahead.

Denied, James turned his persuasion toward Robert’s jacket instead. The weather had been unseasonably warm earlier, reaching the high 60s by late morning. But the air quickly chilled as high winds and a touch of sideways rain passed through the area. Robert was wearing his military green pea coat from Vietnam, his name CAMPBELL across the breast. He took off his jacket and handed it to Baby Boy. James tried it on. Robert was a little huskier, but short too, and the fit was right enough.

They bid goodbye. James, Raney, and their group headed past Northside, walked through the white side of downtown, and ventured to the center of campus for the dance. Robert turned up the block toward his bed. The brisk air wouldn’t bother Robert on his short walk home, and he knew he’d get his jacket back from Baby Boy tomorrow.

IN THE MORNING, Robert Campbell’s grandmother woke him. He was sleeping soundly in his own bed, the planet’s girth between him and Vietnam. He opened his eyes.

His grandmother began gently speaking. She told him that James’s grandmother, Ms. Annie, had just come by the house. She had bad news. “James Lewis is dead,” Robert’s grandmother told him.

Robert was groggy and confused. He responded haltingly. “No … no … no … no … no … ,” he said, thinking it impossible even though he knew how possible it was. “I just saw him last night, Grandma.”

“No,” she said, then she repeated the news, one slow word at a time. “He is dead. There was an accident down there on campus.”

Folks throughout Northside flipped on their radios that morning and heard the news. James’s last name was reported over the airwaves as his mother’s birth name, Trice, but the reality was clear.

Raney Norwood’s mother heard on her radio and woke her son too. He had left the campus dance early to walk his girlfriend home. Raney’s mother told him that James was gone. “That’s impossible,” Raney said to her, “because he was with us.”

James’s funeral was held the day before Thanksgiving at Saint Joseph CME Church on Rosemary Street. On the west side of the church was the block where James had lived his whole life. On the east, the rec center’s block. Across the street, Robert had lent James his Navy pea coat.

Saint Joseph had been central to the early 1960s civil rights movement during James’s youth. People from the neighborhood organized at the church and practiced nonviolent technique on its lawn, as well as at the rec center. Baby Boy was only 11 when the sit-ins began in Chapel Hill, and 15 when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public spaces. But like so many Northsiders, despite fear of reprisals from employers and the employers of family, he had marched too.

James’s grandmother had raised him since he was a baby, and Ms. Annie Cates put so much of herself into that church too, including helping lay bricks during a rebuild. Saint Joseph was founded in 1898. Its mother church, Hamlet Chapel, just a little south across the county line, had been started by formerly enslaved people in 1866, the year after the Civil War. It was the church of Ms. Annie’s youth, when she lived on a tobacco farm with a father born during slavery.

The Saint Joseph pews were full for James’s homegoing ceremony, and the grieving overflowed onto the front steps and lawn. That afternoon Northside community members marched through town in protest yet again. After the trial they’d march some more. It was as it had been all those times in the prior decade when they’d marched to expand the boundaries of their lives.

After the church service James’s casket was driven to Chapel Hill Memorial Cemetery on the edge of town. Robert Campbell, wearing his Navy dress blues, served as a pall bearer and helped walk Baby Boy to his final resting place up on top of the hill. He never saw the pea coat he’d lent James again. Robert and the pall bearers gently set down his friend. He said some prayers. Then he went to the airport, boarded a plane, and flew back to the war on the other side of the world.

[cw: hospital scene]

JAMES LEWIS CATES JR. died about half past 3 a.m. on November 21, 1970, a few weeks after turning 22, surrounded by a roomful of doctors and nurses who didn’t stand a chance. There were too many forces working against them. There were too many forces working against him.

Of immediate concern in that emergency department trauma bay was that when they unwrapped James from the three blood-stained coats desperate bystanders had bundled him in a short distance away, they found he had so little blood left in his body by the time he’d arrived in the backseat of a police car, that they couldn’t get an IV into James’s veins. They had deflated. He had almost no blood pressure. The medical examiner would later testify that James’s body was “almost devoid of blood.” But James’s heart was still trying. So doctors tried first aid. They applied pressure to the approximately one inch-wide wound at his upper groin, hoping to slow the blood escaping his sliced femoral artery as quickly as his dimming heart could pump it. James needed fluids to get his blood pressure back up to anything. They needed to get that needle in. They tried his arm. No luck. They tried a central line at his chest. Still, no. James was unresponsive and hardly breathing. The monitor flatlined. They tried to resuscitate him. Nothing again. James was practically gone by the time he’d arrived, and now it was official.

Forty-six years later, the on-call doctor in that trauma bay, Walter Woodrow Burns Jr., recounted that night as we talked in his home. Chapel Hill had always been a town beguiled by its past, and Burns lived in one of many historical homes named for figures from that past. His was the Coker House, named after its former owner, the botanist who founded the campus arboretum. In 1965, five years before James Cates died, a white woman had been murdered in the arboretum. Justice then had been vigorously pursued, and the memory lived long.

At 78, Burns’s memory of testifying in court had faded. But he still remembered that if James had gotten medical attention sooner he could’ve lived, just as he’d said under oath. He also recalled the stir James’s death caused that weekend, and the urgent questions raised about emergency medical transport. Burns was a resident at North Carolina Memorial Hospital in 1970, but he had interned at a Naval hospital in San Diego, working on wounded service members flown over from Vietnam. Even so, that night in Chapel Hill still stood out all those years later. “When you lose somebody under those circumstances,” he said, “I don’t think you ever forget it.” Forget is what Chapel Hill did though, at least outside the boundary that James Cates, his friends, his family, and his neighbors knew well.

For details on the circumstances of Mr. Cates’s death, read here or listen here.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

Author interviews and conversations with friends, neighbors, and relatives of James Cates Jr., as well as contemporary newspapers, oral histories, and documents from the University Archives, U.S. Census, Orange County Register of Deeds, and elsewhere.

Photos:

Chapel Hill High School yearbook, 1967, courtesy of Sarah Geer

Youth baseball team photo, Chapel Hill Herald, May 10, 1998

Graham Street sign and Saint Joseph CME Church, by Mike Ogle