STONE WALLS is grateful to welcome kynita stringer-stanback as a guest writer for this edition of the newsletter, and the next. stringer-stanback is a descendant of November Caldwell and his son Wilson Caldwell, important local historical figures, and she has a powerful story to tell. It reaches back to two of UNC’s first presidents who enslaved her ancestors. Her incisive article, “From Slavery to College Loans,” will be published by Stone Walls in two parts with full bibliography. The article originally appeared in 2019 in Library Trends, a peer-reviewed academic journal of Johns Hopkins University Press. stringer-stanback owns the copyright to her article and has agreed to republish it here. The text appears essentially the same as its original version, with a new author’s note added that potentially calls into question the previously known record for the parentage of Wilson Caldwell.

Part I is below. (Read Part II.)

kynita-stringer stanback is an information activist.

From Slavery to College Loans

By kynita stringer-stanback

ABSTRACT

MY STORY BEGINS back in 1793 when November Caldwell was “gifted” to Helen Hogg Hooper (whose father-in-law, William Hooper, signed the Declaration of Independence), the wife of the first president of UNC, Joseph Caldwell. November Caldwell is my great-great-great-grandfather. Currently, I owe over six figures in student-loan debt to the very institution that enslaved my ancestors. We are at a particular place in the political history of our nation. White supremacy is morally corrupt. It requires that we deny the humanity of human beings for one reason or another. It is hard to stand up against white supremacy because folks who do are often ostracized from their families and communities. We have all been socialized to believe in white supremacy—it was one of our nation’s founding principles. In this essay I hope to break open a dialogue about the white supremacist hegemony institutionalized within our neoliberal university system. Connecting the past atrocities of slavery with actual educational experiences of the descendants of those who served the proslavery institutions has not been widely publicized or talked about. We must interrogate our history or we will be doomed to continue to repeat the horrific inhumane atrocities.

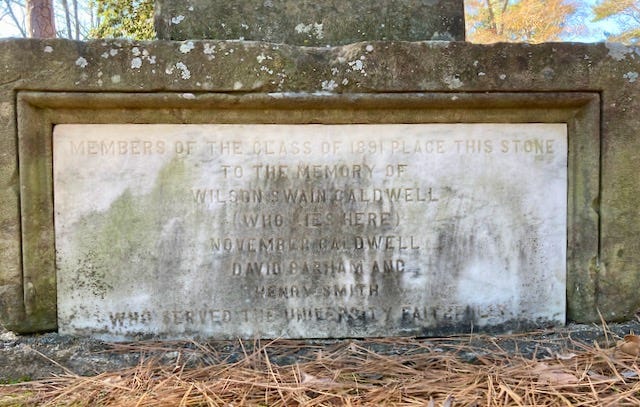

IT ALL STARTED May 1992. My father was taking me to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to participate in a recruitment program for talented Black students from across the state. Prior to dropping me off at my destination, my father took me to a graveyard behind Connor Dormitory on UNC’s campus. There was a gazebo and small paved path that separated one side of the graveyard from the other. My father told me that whites were buried on the side with the gazebo, and Blacks were buried on the other (even in death, Jim Crow was a necessary evil). He took me to an obelisk that had four names on it:

November Caldwell

Wilson Caldwell

David Barham

Henry Smith

Dad told me that November and Wilson were our ancestors. He said that we had been here all along. November and Wilson were born into slavery, lived through emancipation, and emerged as free men.

UNC was the first public university in the nation. The cornerstone for UNC was laid in 1793. It was the only public university in the United States of America to confer degrees in the eighteenth century. Curiously, absent from the brief history of UNC on its website was the displacement of Indigenous Nations that occupied the land on which the school was built as well as any mention of coerced chattel labor, like November and Wilson.

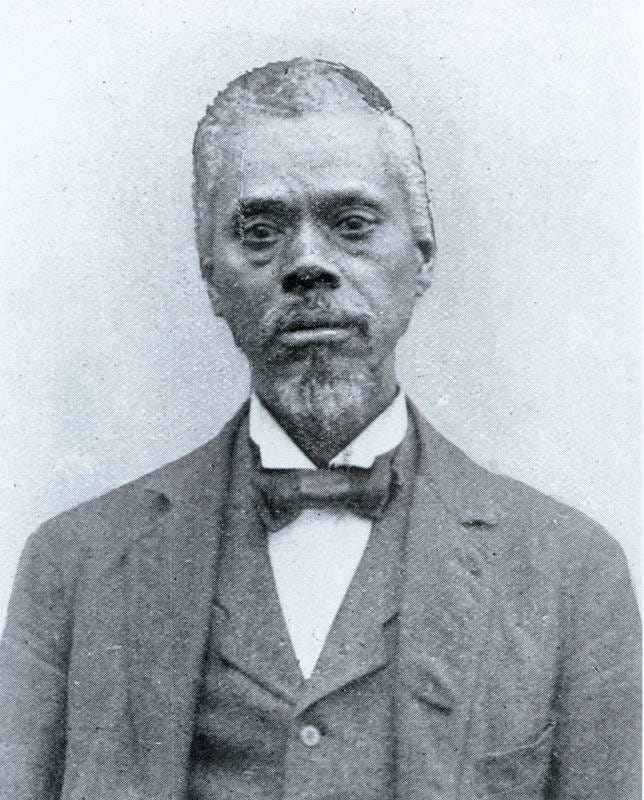

November Caldwell was the coachman for Joseph Caldwell, the first president of UNC. During Reconstruction in 1869, his home was terrorized by a Ku Klux Klan mob. Wilson Caldwell, November’s son with Rosa Burgess*, helped save the university from annihilation by the Union soldiers. His ambassadorial skills saved the university from being burned to the ground.

I began my research about my familial connection to UNC in earnest after moving across the country to accept a job in an academic library. I realized and reflected upon the fact that my student-loan debt had ballooned to six figures while I was still unable to earn a salary commensurate with such an enormous debt.

During my research in the University Archives at UNC, the only reference to Rosa Burgess was as Wilson’s mother and wife of November Caldwell (Battle 1895). There is nothing in the university archive that describes, nor honors her life and contributions to UNC. Outside of references with respect to my male ancestors, very little is available within the UNC archives about Rosa Burgess.

Rosa Burgess and Susan Kirby (wife of Wilson) both lived under the partus sequitur ventrem legislation. Partus sequitur ventrem, translated from Latin, means “birth follows womb.” Essentially freedom was attached to motherhood. If the mother was enslaved—the law stated that her children would also be enslaved.

Rosa Burgess and Susan Kirby were married to November and Wilson, respectively. Rosa was Wilson’s mother.* Rosa and Susan did not have control or agency over their bodies. They were forced to procreate to create wealth for the agents and leaders of the nation’s flagship public university.

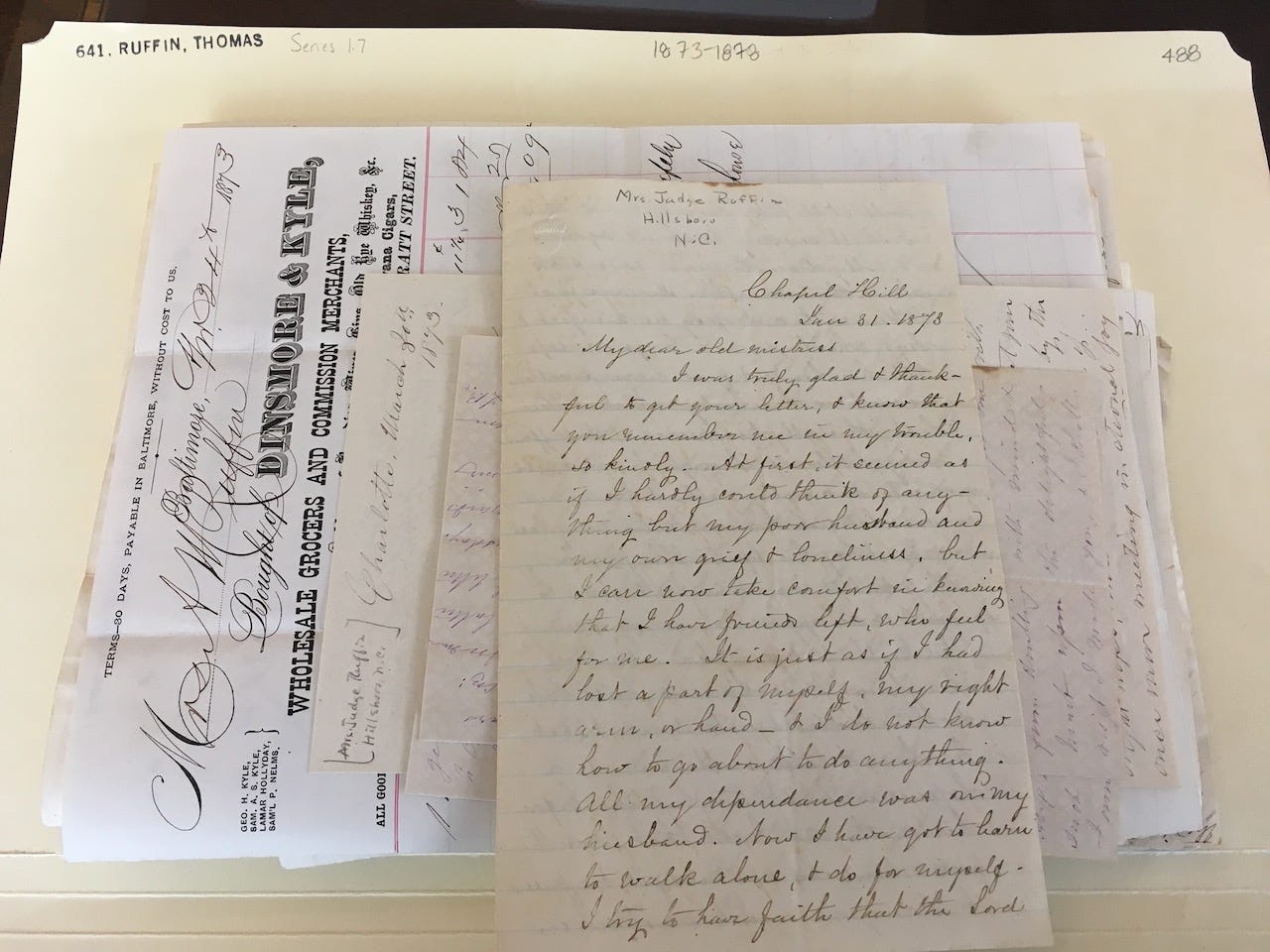

* AUTHOR’S NOTE: A woman named Charity is the only woman I found in written documentation at the Southern Historical Collection with a connection to November Caldwell (based on my family members’ articulation of their history). In fact, Charity addressed a letter to Judge Thomas Ruffin’s widow about November Caldwell’s passing on Christmas Day 1872. In the letter, Charity Caldwell called November her husband and signed it “Your attached old servant”. She wrote about November’s death and her plight to keep their land in the wake of his passing. Further research has raised the question as to whether Charity, and not Rosa Burgess as has been widely assumed based only on Kemp Plummer Battle’s telling, could’ve been the mother of Wilson Caldwell. Finding records of my womb tree (my ancestral mothers antebellum) has proven to be next to impossible.

According to the law, enslaved women were property. Their wombs were seen as factories to produce wealth for their “masters.” Any children born to my ancestral grandmothers were considered property. Any children born to November Caldwell and Rosa Burgess “belonged” by law to President David Lowry Swain.

My great-great grandfather, Wilson Swain Caldwell, was therefore the property of President Swain. President Swain purchased Rosa Burgess from Governor Iredell. Legally, Wilson Swain’s surname was Swain because he was the legal property of President Swain.

Yes, the powerful and wealthy men of their ilk (men with their names on many of the buildings at UNC)—leaders of the great state of North Carolina—were conceivably law abiding rapists.

Once emancipated, my great-great grandfather, Wilson, changed his surname to Caldwell, to match that of his father—November. Wilson and Susan gave birth to my Great Grandfather Bruce Caldwell. Bruce was my Grandmother Catherine Constance Caldwell Stanback’s father. Bruce Caldwell married Minnie Stroud. Minnie Stroud’s mother was Emma Kelly—Emma Kelly was the only female ancestor from my father’s womb tree that was not listed with a spouse.

My grandmother, Catherine Caldwell Stanback, described her grandmother as very light skinned with green eyes and straight hair. Though partus sequitir ventrem was no longer the law of the land, paramour rights were a terrorizing reality for women of my great-great grandmother’s generation. In theory Jim Crow laws were created to keep Blacks and whites socially separated. White men, especially white men in the South, lived in a society where they had carte blanche access to Black women. White men were not compelled to offer Black women and their daughters the liberty of freedom from intimate and bodily violations on a daily basis. The great leaders of this state felt it more important to be able to legally and socially rape Black women rather than confer the right and respect to be able to consent to sexual intercourse.

During Reconstruction, Wilson Caldwell was appointed as a justice of the peace in Chapel Hill. This meant that this Black man, my great-great grandfather, adjudicated disagreements between residents—Black and white. He held the position for a year.

In 1869, November Caldwell’s home was stoned by a mob of the Ku Klux Klan. In fact, by 1871, the United States Government had launched a Congressional investigation in order to ascertain the depth and breadth of KKK activity throughout the South. Dr. Pride Jones, the person in charge of the investigation of the KKK in Orange County, refused to provide names or specific incidents related to KKK activity, and no record of the attack on November Caldwell was listed. Shortly thereafter, Wilson was removed as Chapel Hill’s first Black justice of the peace.

As noted in Wilson’s biography by Kemp Battle, Wilson left Chapel Hill for Durham in the hopes that he would be able to earn more money to support his wife and children. Wilson Caldwell and Susan Kirby had a total of twelve children, but seven died. What living conditions were Wilson and Susan subjected to that contributed to the deaths of seven of their twelve children? Five of the seven children died from consumption (now known as tuberculosis). The silence is the violence.

Chapel Hill was considered to be more genteel and kind to human chattel—some would even opine—overindulgent. Wilson Caldwell was literate, and during slavery (his formative years) it was illegal to teach a slave to read. It was Wilson, along with the white leadership of the university, who advocated for and received the benevolence of the Union soldiers (perhaps giving the general a bride helped—as he could not justify the pillaging of his betrothed’s homeland). Wilson was emancipated after the Civil War. David Lowry Swain was mortally wounded in a riding accident—he was thrown into a tree by his horse, and Wilson cared for him until his death.

In 1992 during my first visit to UNC, I did not understand just how rooted and connected to the university I was. My ancestors toiled the land. As the reality of my six-figure student-loan debt with compounding interest loomed over my psyche, I dug deeper into the research. It inevitably spelled out how intimately and intricately my ancestors were connected to the building, growth, and preservation of our nation’s flagship public university. Outside of the segregated graveyard obelisk, nothing stands to recognize their service, sacrifice, and commitment. Not one building, statue, or monument on that campus stands without screaming the blood of their sacrifice.

THE STATUE that stood prominently on campus during my undergraduate career at UNC was not a statue that honored the Black people who helped build, sustain, and ultimately save the school, but instead Silent Sam, a symbol of the Confederate soldiers who fought to keep my ancestors as chattel and coerced labor both physical and biological.

How many of the descendants of the Iredell, Caldwell, and Swain families graduated from UNC? Did they owe student loans?

June 2000, I had relocated to rural North Carolina after my maternal grandmother, Betty Jean Stringer (Nana), passed away. Her death was unexpected. She was the anchor of my mom’s family. Her death left me feeling aimless, with little direction and no clear path to a career. I moved to DC and started working in the nonprofit sector but ended up working at a local gym. Prior to Nana’s passing in March 2000, we had a difficult conversation about me coming out as a lesbian.

The caveat: prior to going to North Carolina my first year in 1993, Nana told me, “Don’t go down there to Chapel Hill and let them girls turn your head around.” At that time, I had no idea what she was talking about. I wasn’t even out to myself. I had no idea I was queer. I always had really intense relationships with my female friends, but it was never romantic. That all changed in undergrad.

I realize, now, that my grandmother was concerned about my ability to survive. She was concerned that I would be prejudged about my ability or completely disregarded because I was (in her words) “choosing to be different.” We argued about choice. I told her that who I was was not a choice. She saw something in me before I could see it within myself for myself.

I sent her a Valentine’s Day card that year and later followed up with a phone call to check on her after she had gotten home from the hospital (I mean who stays mad at their grandmother?). She said she knew the card was from me as soon as she opened it. We laughed and talked. We told each other we loved each other and exactly one week later, March 22, 2000, she passed away in her sleep at home while my grandfather was at work.

When I went home for her funeral, she had stuck my card next to the telephone in the wall. She looked at it every day. My grandparents loved me so much. It was their love that showed me, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that I mattered. They taught me that I did not have to submit to those who sought to oppress, repress, and subjugate me in any way.

I was among the first generation of women from my womb tree who was born with the right to vote, the right to demand and expect consent, and the right to choose how and if I wanted to biologically reproduce in the history of our nation. Think about that.

Black women were not afforded the right to vote until 1965. If you have a Black mother who was born before 1965, and you are female, you are among the first generation of your womb tree to be afforded the right to vote from birth (especially and specifically if you’re from the South.)

I WAS UNEMPLOYED, so I went to the Employment Security Commission down in Rowan County, North Carolina. The person behind the desk took one look at my degree, my employment profile, and me, and said, “You look like a rebel, you should work in a library.” She recommended that I apply for a job at a small theological library. I was hired on the spot as a library technical assistant. I worked at three libraries over the next four years and decided to go teach English in South America. I came back from South America, fluent in Spanish. After I had landed another job in a public library, I thought it was time for me to pursue a graduate degree in the field.

My first reference question did not come during my first job in a library. In fact, it came when I was six or seven years old. My mom and grandparents encouraged me to learn about Black history and to do my book reports on Black historical figures. Harriet Tubman was my favorite historical figure. Madam CJ Walker, Shirley Chisholm, Malcolm X, Septima Clark, and Frederick Douglas were just some of the historical figures my family thought I should know about. I was an advanced reader.

My mom purchased The New Book of Knowledge encyclopedia set for me and my brother. She painstakingly and patiently taught me how to use the index—find the volume and page numbers that led to the entry I sought. We practiced once or twice (it didn’t take me long to understand), and from that day on, any time I asked my mom anything that she thought could be found in those volumes, she would say, “Look it up!” An encyclopedia set for a single mother of two was a major financial sacrifice and Betty A. Stringer (my mom) was not about to let her investment sit on the shelves and collect dust. She made sure I used them weekly, if not daily.

My mom was a single parent with two children. She taught me to be independent. I was never really allowed to go over to my friend’s homes, and if they wanted to play with me on the weekends, all play dates happened at our house. A friend from school came over one Saturday for a play date and announced she was having a little brother or sister. She asked me if I knew where babies came from. I told her I did not, but that we could look it up. That Saturday, I conducted my first reference interview. We looked up various terms—I can’t remember them all—reproduction was one of them. We ended up finding the entry for “baby.” We learned about chromosomes, zygotes, ovaries, and sperm. We mispronounced some of the terms to one another. I remember giggling and trying not to make too much noise to arouse attention or suspicion of surreptitious activities. After she left, I had so many questions for my mom.

It was on that blessed day that I inquired about the person who contributed the other half of my chromosomes for the first time. I asked my mom, “Where did the other half of my chromosomes come from?” She answered my question with a question of her own, “What have you been reading?” I said, “the encyclopedia.” She hugged me and took me to the library to get more kid-friendly books on reproduction.

A few days later, my father came to our house and introduced himself over dinner. I met my father, A. Leon Stanback, Jr. Biology led me to my father—later on in my life I learned that my father was a chemistry major in college. The divinity, majesty, and serendipity of nature, research, and science converged and led me to my dad.

My father was a lawyer who went on to serve our state as a parole commissioner, a superior court judge, and ultimately a district attorney. He was running to be a district attorney the year I was born. He lost. He was appointed to positions to serve as a respected jurist and prosecutor by Republican and Democratic governors. After a career of over thirty years as legal professional, he retired.

As my father was ending his professional career as a jurist (he retired in 2009), I began my professional career as a librarian. Up to that point, I had served as a library assistant, library technical assistant, and documents assistant. I graduated from UNC with a master’s of science in library science, with a concentration in international development, and with awards for exceptional expository composition.

My first job out of graduate school was as a diversity resident librarian/research assistant professor. I published an article and helped write an ARL (Association of Research Libraries) Spec Kit. I served on committees, participated in conferences, and went to one of the most respected leadership-training institutes for early career librarians. I took classes in grant writing, quadrupled the number of faculty who participated in our institutional archive (repository), and provided reference assistance at two separate service points in the library as well as provided virtual chat reference. Did I mention I speak Spanish? It took five years after my two-year residency ended to find employment.

I challenge and question authority. As a gender-nonconforming, queer, person of color who identifies as female, I have to be keenly aware of my environment.

What does this have anything to do with my college loans? After I completed my graduate degree at UNC, I graduated with over $90,000 in debt. It’s hard to pay back a loan when it’s more than double your yearly income. My first position was only a two-year appointment.

[Part II]

The article’s full bibliography is below.

ONE GOOD THING:

A new episode of the “Re/Collecting Chapel Hill” podcast is out, this one in the voice of CJ Suitt, Poet Laureate of Chapel Hill.

Also check out the video for Suitt’s recent poem “In The Aftermath” as well as one from several years ago, “My Little College Town,” that aligns with the subject matter of Stone Walls.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

Originally published:

LIBRARY TRENDS, Vol. 68, No. 2, 2019 (“Labor in Academic Libraries,” edited by Emily Drabinski, Aliqae Geraci, and Roxanne Shirazi), pp. 316–29. © kynita stringer-stanback

References:

Barnett, Ned. 2018. Letter to the editor. News & Observer (Raleigh, NC), August 21, 2018. https://www.newsobserver.com/opinion/article217070510.html.

Battle, Kemp P. 1895. Sketch of the Life and Character of Wilson Caldwell. Chapel Hill, NC: University Press. https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/slavery/item/3640.

DiAngelo, Robin. 2018. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston: Beacon Press.

Documenting the American South. n.d. “David Lowry Swain, 4 Jan. 1801–29 Aug. 1868.” Accessed September 29, 2018. https://docsouth.unc.edu/browse/bios/pn0001638_bio.html. Original source: Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, edited by William S. Powell.

Documenting the American South. n.d. “Original Joseph Caldwell Monument (Wilson Caldwell (Grave).” Commorative Landscapes. Accessed September 29, 2018. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/48/.

Fortin, Jacey. 2018. “U.N.C. Chancellor Apologizes for History of Slavery at Chapel Hill.” New York Times, October 13, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/13/us/unc-carolina-apologize-slavery.html.

Gordon, Taylor. 2015. “10 Pieces of Evidence that Prove Black People Sailed to the Americas Long before Columbus.” Originally posted on Neo-Griot (blog). January 23, 2015. Accessed March 22, 2019. https://www.lahc.edu/studentservices/aso/bsu/knowyourhistory/10PiecesofEvidenceThatProve.pdf.

Hamer, Fannie Lou. 1967. To Praise Our Bridges: An Autobiography. Edited by Julius Lester and Mary Varela. Jackson, MS: KIPCO. https://snccdigital.org/wp-content/themes/sncc/flipbooks/mev_hamer_updated/index.html?swipeboxvideo=1 - page/10.

Hudson, David James. 2017. “On ‘Diversity’ as Anti-Racism in Library and Information Studies: A Critique.” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 1 (1): 20–21. https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v1i1.6.

Macedo, Donaldo. 2006. Literacies of Power: What Americans are not Allowed to Know. Boston: Westview Press.

North Carolina General Assembly, “Resolution 2007–21, Senate Joint Resolution 1557,” April 12, 2007, https://www.ncleg.gov/Sessions/2007/Bills/Senate/PDF/S1557v3.pdf.

The 168 Congress Joint Select Committee. 1872. Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into theCondition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States: North Carolina. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office). https://archive.org/stream/KKK1871CongressionalTestimony/North Carolina - mode/2up.

Out and Equal Workplace Advocates. 2017. “2017 Workplace Equity Fact Sheet.” http://outandequal.org/2017-workplace-equality-fact-sheet/.

Southern Poverty Law Center. n.d. “Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.” Accessed January 10, 2019. https://www.splcenter.org/sites/default/files/tt_hard_history_american_slavery.pdf.

Spruill, Brittany, Erienne Jenkins, and Brooke Parker. 2013. “Monuments and the Spaces They Occupy.” Commemorative Landscapes. Documenting the American South. https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/features/essays/spruill/ - bottom5.

Turner, Cory. 2018. “Why Public Loan Forgiveness is So Unforgiving.” WUNC 91.5. Transcript of October 17, 2018, NPR Morning Edition broadcast. http://www.wunc.org/post/student-loan-whistleblower.

UNC (University of North Carolina) Archives. 2018. “David Barham died on this day in 1860 . . . .” Twitter, June 22, 2018, 6:14 AM. https://twitter.com/uncarchives/status/1010148922415828992.

UNC–Chapel Hill (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). n.d. “History of the University,” History and Traditions. Accessed January 10, 2019. https://www.unc.edu/about/history-and-traditions/.

———. n.d. “November Caldwell (1791–1872).” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed September 29, 2018. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/slavery/drawing-of-november-caldwell--.

———. n.d. “Wilson Caldwell (1841–1898).” The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Accessed September 29, 2018. https://museum.unc.edu/exhibits/show/slavery/wilson-caldwell--1841-1898-.

Wilder, Craig Steven. 2013. Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery and the Troubled History of America’s Universities. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Woods, Clyde. 2017. Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta. New York: Verso.

Photos:

Photo of Charity Caldwell’s letter to Anne Ruffin, taken at the Southern Historical Collection, by kynita stringer-stanback

Wilson Caldwell photo — The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History

All other photos by Mike Ogle