YES, Chapel Hill, there has been a coup here. Fear of a stolen election is on a lot of minds right now at a national level as Election Day 2020 arrives. But locally, it’s happened to Chapel Hill’s leaders. Government overthrows don’t have to be by tanks and guns. Attorneys, courts, and government officials can provide the firepower and a mirage of legitimacy. Though it certainly helps to have the distinct possibility of violence, as we do today. In North Carolina, we’ve also had the Wilmington Massacre. (For more on Wilmington’s parallels to today, read my friend Michael Graff of Charlotte Agenda on Trump’s Proud Boys debate comment.) Let’s also not forget that four years ago Governor Pat McCrory refused to concede his clear loss for a month.

Chapel Hill’s coup d'état occurred 150 years ago, in 1870, but otherwise the circumstances also had a surprising amount in common with 2020. Technically, it wasn’t a violent takeover — but only technically — and unlike Wilmington, this one didn’t last. But ingredients similar to today were brewing in the air. Hate groups had organized and emboldened. Violence and its implicit threats surrounded. Election misinformation and intentional disenfranchisement were employed. Lawyers mobilized. And it was all driven by racist animus in a backlash to diminished white power.

A POWER struggle transpired in Chapel Hill for many years after the Civil War. It ultimately ended with conservatives prevailing, retaking control of UNC, and thus the town. But in the first post-war years, the Republicans of Reconstruction had the upper hand. That fact did not sit well with a large and loud segment, especially because Black people held some local government positions. Terror was the chief weapon of dissent, and Chapel Hill “became a center of organized white resistance,” wrote James Vickers in his book Chapel Hill: An Illustrated History.

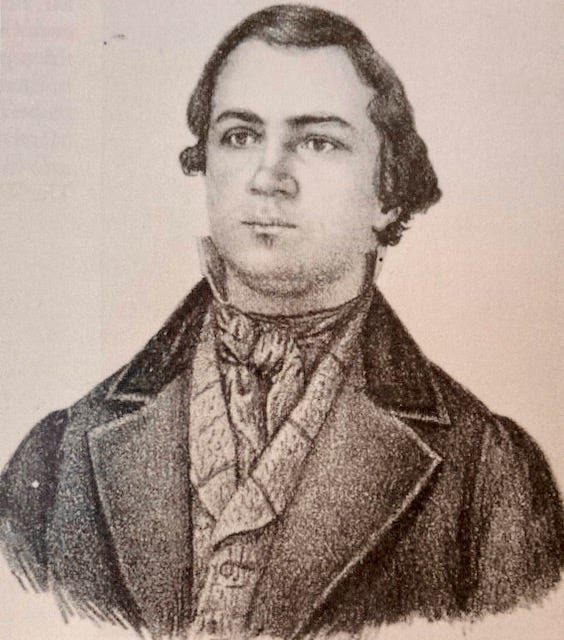

William L. Saunders, Chapel Hill resident and head of the state Ku Klux Klan. He served long tenures as a UNC trustee and North Carolina's secretary of state.We all now know from the renaming of UNC’s Saunders Hall that William L. Saunders led from Chapel Hill the North Carolina Ku Klux Klan’s efforts in that period. Nearly half the village’s people were Black then, yet the fact that some Black men held positions of authority, including as town commissioners and in law enforcement, was an outrage to many.

Klan and other violent white supremacist activity was all over North Carolina, but especially prevalent in this region of the state. “In various counties there were brawls, night-ridings, and whippings,” according to The Woman Who Rang The Bell. Whether a particular outing by white supremacists was violent or more subdued, all carried the clear purpose of intimidation. Yonni Chapman wrote in his dissertation on local Black history: “Throughout 1868 and early 1869, the Klan engaged in hundreds of beatings and other attacks on African Americans and white Republicans in counties adjoining Orange. A virtual state of war existed between the Republican administration in Raleigh and thousands of Klan nightriders in central North Carolina.” Multiple documented lynchings occurred in Hillsborough at this time, as local scholar Paris Miller recently detailed in her presentation for the “History of Racial Terror” session of the Ida B. Wells symposia.

UNC’s president, also a Chapel Hill commissioner, asked the governor for military assistance. A local lawyer, and town clerk, pleaded for help in a letter to the governor, writing that it had become common for dozens of masked Klansmen to be “rowdying up and down through the streets of this village” around midnight. Sometimes they’d just ride silently like ghosts down Franklin Street, their horses’ hooves muted in the dirt. One particular night, between 50 and 200 of the Klan rode through town beating Black people. They forced one, a political leader, to vow support for the Democrats. They also terrorized Black people in a poorhouse; broke into the home of Henry Jones, the Black constable; and stoned the house of November Caldwell, whose son Wilson was justice of the peace.

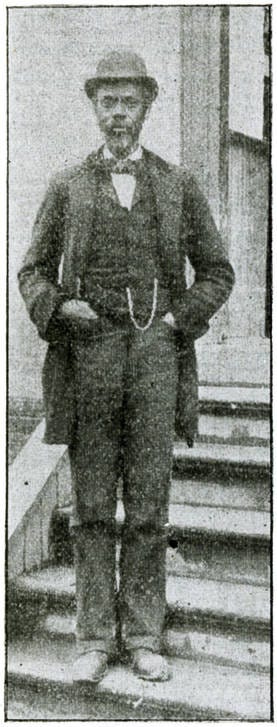

Wilson Caldwell, justice of the peace. Wilson and his mother, Rosa Burgess, had been enslaved by UNC president David L. Swain. His father, November Caldwell, was enslaved by UNC president Joseph Caldwell.With violence rampant and terror pervasive, the governor sent detectives out into the state to investigate the Klan. One detective was dragged from his hotel in Chapel Hill, strapped to the town pump in front of where University Methodist Church is today, and whipped, receiving 60 lashes to his naked back. The detective later charged the white magistrate of police for leading the beating.

The terrorists were either trying to dissuade the governor from further political interference, or practically daring him to take firmer action to escalate the political stakes of the conflict. Eventually, Governor William W. Holden did, signing a proclamation threatening military intervention against vigilante insurrections. He followed through on the promise in Alamance and Caswell counties and broke the Klan, but was impeached as a result.

CONSERVATIVES in Chapel Hill made their big move just after the governor’s proclamation. A few months prior, in the fall of 1869, a local group had met and then loudly announced their grievances in newspapers around the state. Their gripes included outrage over the fact that Chapel Hill had a Black justice of the peace, Wilson Caldwell, and a Black constable; and that having Black political officials in general caused “an unnecessary antagonism.” They were also angry that the governor had sent armed Black soldiers to secure the safety of the campus.

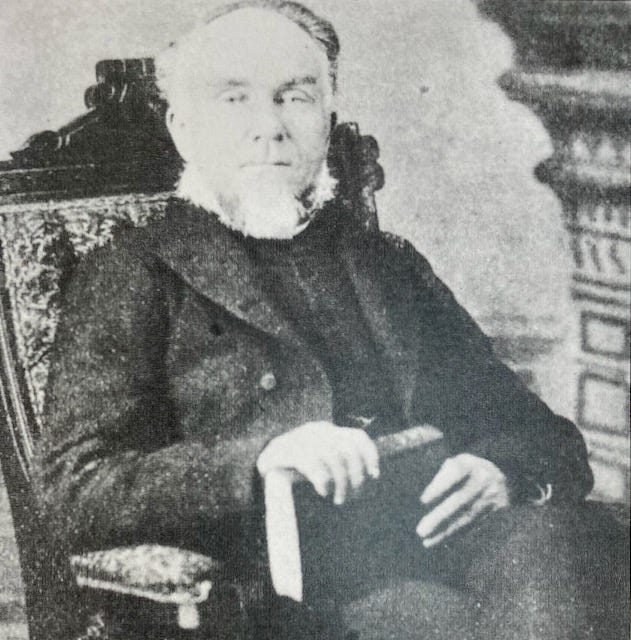

Solomon Pool, the largely despised Reconstruction-era president of UNC and member of the village's Board of Commissioners. UNC later closed for four and a half years as a result of local and statewide spite over Republican university leadership.The village’s government was rather representative of its residents though. Its Board of Commissioners included UNC’s president, a Black shoemaker, a white farmer, and a Black farmer. A white farmer was magistrate of police, and the vice constable was a Black man.

But on February 28, 1870, with all that violence as a backdrop, the disgruntled group of conservatives conspired to hold a phony election. With their fake votes, under no legal authority except an “informal notice” by an aligned attorney and state legislator, they “elected” their preferred town commissioners, who installed their preferred magistrate of police and constable. They stole the government’s official books and papers and began holding regular meetings to conduct the village’s business.

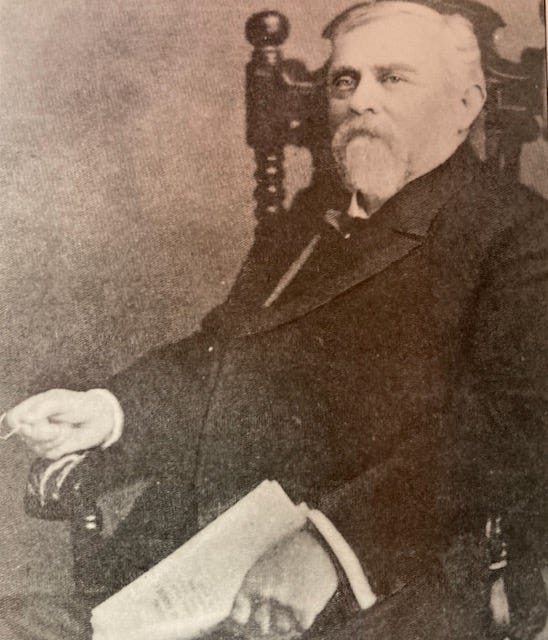

Thomas M. Argo, attorney and close and personal Klan ally, helped the rump commissioners execute their phony election. He was a state legislator at the time.This went on for about a month. But by early April the rightful board of commissioners gathered themselves to push back. (The meeting minutes from their discussions on March 30 and April 1 of 1870 are available online in the Town of Chapel Hill archive.) The town clerk recorded that “certain citizens of the village … were claiming to be the municipal officers of the village.” The legitimate board tasked UNC’s president with confronting the fake board, a “rump” board, with legal evidence that they were illegitimate. That was done, and the fake board’s attorney conceded the point.

Minutes from the Board of Commissioners meetings on March 30 and April 1, 1870, discussing the coupThe true Board of Commissioners decided, in a typical and unwise act of placing white civility above all else, that if the rump board returned the stolen books and papers, the government would let it all go, no harm no foul. Everybody would move on. And so they did. People involved in and connected to the takeover and the Klan activity continued playing influential roles in official town business, including Saunders, the head of the state KKK. The conservatives eventually wrestled back control of UNC and Chapel Hill.

ONE GOOD THING:

Elizabeth Cotten is watching.

Do give a listen to the terrific new episode about her from the “Re/Collecting Chapel Hill” podcast.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

As is often the case, I first learned about the coup from Yonni Chapman’s dissertation, then followed up with his sources and others.

“Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960,” doctoral dissertation by John K. (Yonni) Chapman, UNC-Chapel Hill (2006): UNC Libraries

Chapman’s footnote: Minutes from February 28, March 3, 21, 30, April 1, 7, Minute Book of the Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners, 1869-1885, at Chapel Hill Town Hall, Chapel Hill, N.C.; Vickers, Chapel Hill, 83. [Note: The minutes to the board meetings during the first few weeks of the coup, apparently minutes of the rump board, were not available in the Town of Chapel Hill’s online archive as of the time of the writing of this post.]

From the dissertation: “In February 1870, building on the foundation prepared by terror and propaganda, this same group attempted to overthrow the Republican Board of Commissioners in Chapel Hill. The group organized a fraudulent election on February 28 and installed a new Board of Commissioners that included John H. Watson, David McCauley, J.F. Freeland, John R. Hutchins, and W.J. Newton. Four of these men had been organizers of the September protest meeting. They seized the town records and began meeting, appointing members of their group as Magistrate of Police, Town Constable, and Town Clerk. Nevertheless, this attempted takeover stalled in early April, following a meeting of the Conservatives with a committee headed by Solomon Pool. Pool reported to the Republican commissioners that the Conservatives had held their election without a written copy of “any Act of law authorizing it.” The men had acted “under informal notice from Mr. T.M. Argo that such an election should be held.” The takeover of Chapel Hill government by Conservatives collapsed completely on April 7, when their own attorney informed them that the February 28 election was not valid. The full story of this attempted coup in Chapel Hill remains to be told.”

Minutes of 1870 Chapel Hill Board of Commissioners meetings: Town of Chapel Hill archive

Chapel Hill: An Illustrated History by James Vickers

Images of America: Chapel Hill by James Vickers

The Woman Who Rang the Bell: The Story of Cornelia Phillips Spencer by Phillips Russell

“Argo, Thomas Munro”: NCpedia

“A Proclamation. By His Excellency The Governor of North Carolina.” The Hillsborough Recorder, April 6, 1870

“Public Meeting.” The Hillsborough Recorder, April 27, 1870

“The Election That Could Break America” by Barton Gellman: The Atlantic

“Election Violence in the United States is a Clear and Present Danger”: Foreign Policy

“Why the president’s Proud Boys comment hit home in North Carolina” by Michael Graff: Charlotte Agenda

Wilson Caldwell photo: The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History, UNC

William Saunders, Solomon Pool, and Thomas Argo photos: Images of America: Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Cotten mural photo: Mike Ogle

Mike, although the pretenders were evidently never prosecuted for this coup, it appears that they perhaps did not return the papers of the Town. The 1869 town minute book cited above is the earliest one still in the possession of the Town of Chapel Hill - presumably because of this incident... -Mark Chilton