PERHAPS the U.S. Supreme Court case more Americans know than any other is Brown v. Board of Education. But we don’t often learn a lot about the snail’s pace with which the landmark 1954 decision was implemented. Or how many tricks white people pulled in resistance.

The battle to desegregate schools seemingly never ends. It led to the explosion of private schools, and heavily influenced white families fleeing for suburbs. As a result, schools are more segregated now than they were in 1970, and the problem has been worsening since 1980. While the condition is hardly confined to the South, that was where the most public fights took place in the wake of Brown v. Board. North Carolina and Chapel Hill were no exceptions.

We’re now in (remote) back-to-school time here, so let’s take a local look at one aspect of that protracted battle, North Carolina’s Pearsall Plan. Back in 1956, the rhetoric of school choice, redistricting/seceding, and vouchers prevalent today had taken hold. (See this 2017 article “The Resegregation of Jefferson County” on secede tactics.)

ON SEPTEMBER 8, 1956, North Carolina held a special election on a Saturday to vote on a few amendments to the state constitution. The main one, which had just been the subject of a four-day special session of the General Assembly, was drafted to neutralize Brown v. Board. The amendment was called the Pearsall Plan for the ex-legislator who headed the all-white committee that developed it. “The Pearsall Plan to Save Our Schools” was an antidote to integration.

The Pearsall Plan would give white parents two off-ramps: the ability to opt out of public schools with a voucher for private school tuition, and a mechanism by which districts could halt operations and re-organize themselves if Black families insisted on integrating. The General Assembly even passed a law making school attendance no longer compulsory in case of integration. As one Chapel Hill newspaper explained, other states in the South “goaded by U.S. Supreme Court decisions attacking segregated schools” had already developed plans to close schools “before Negro children are accepted in any white schools.”

[NOTE: The town newspapers of that era, the Chapel Hill Weekly and the Chapel Hill News Leader, have not been digitized. These images are photographs of the bound volumes at the Chapel Hill Historical Society. The Daily Tar Heel had not yet begun publishing for that fall semester.]

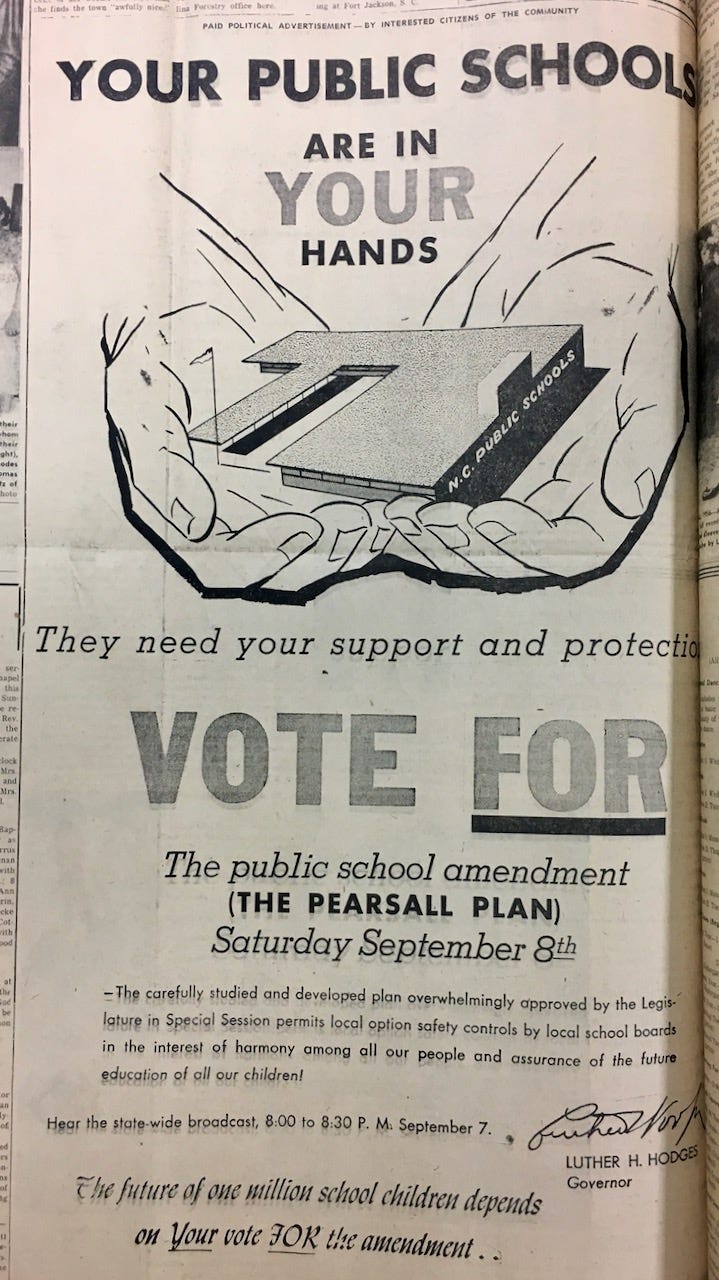

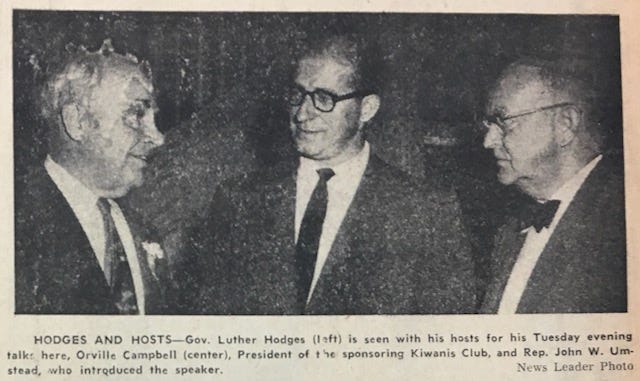

Half-page ad endorsed by the governor in the Chapel Hill News LeaderGovernor Luther H. Hodges was an enthusiastic cheerleader of the Pearsall Plan, and days before the vote he stumped for it in Chapel Hill. He spoke to an all-white crowd of hundreds in UNC’s Carroll Hall, and then at a dinner at the Carolina Inn with the Kiwanis and Rotary clubs. At both events, the governor was introduced by North Carolina Rep. John W. Umstead Jr. of Chapel Hill, a fellow Pearsall-backer. (Umstead was a wealthy insurance executive, the son of a Confederate veteran, and brother of the governor who preceded Hodges but had died in office while advocating against integration post-Brown.)

The Pearsall Plan had earned four especially vociferous critics in Chapel Hill. So as Gov. Hodges’ (white) opponents appeared with him at the event, civility was emphasized by the men and the local press as ruling the day. The governor made a point of saying that the critics “who have resorted to name-calling in their attacks upon people whose views differ from theirs” were not connected to UNC. Hodges and his (white) critics shared a laugh on stage about the tension. They could agree to disagree! Politics, amirite!

“Afterwards—A friendly handshake”The two town newspapers were split on Pearsall, although the one in favor, the Chapel Hill Weekly, was much louder about it. Interestingly, the Chapel Hill News Leader identified Orville Campbell in a photograph as a host of Gov. Hodges, yet described Campbell only as the president of the Kiwanis Club. Campbell was publisher of the rival paper.

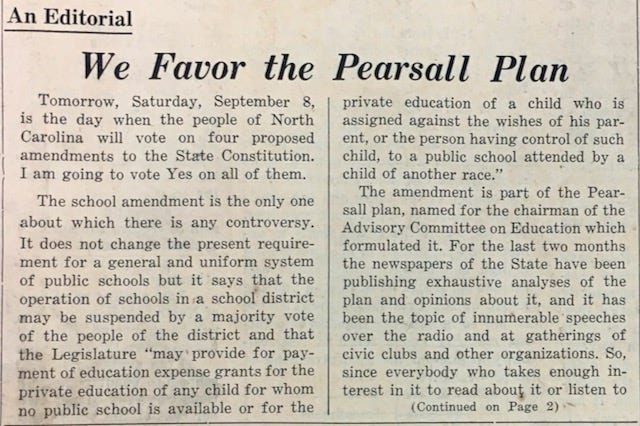

Gov. Hodges (left), Orville Campbell (center), and Rep. John W. Umstead (right)The Weekly’s story on the speech did not mention its publisher’s involvement, and it ran an editorial endorsing the Pearsall Plan on its front page. The editorial quoted the chairman of the State Commission on Higher Education calling the unanimous Brown decision “abhorrent.”

Chapel Hill Weekly front-page editorialAnother article in the Weekly defined integration as “letting down the bars and permitting colored children the privilege of attending white schools.” For its part, the News Leader ran on its op-ed page a short editorial, “Will Fears Determine This Election?” It implied people should vote against Pearsall but without explicitly endorsing that position. Nearly half the front pages of both papers were dedicated to the issue, plus plenty more inside.

During the question-and-answer following the governor’s speech in Carroll Hall, several who opposed Pearsall still made a point to say they were “not one of those questionable individuals in Chapel Hill.” One of those outspoken critics was a Black minister, Rev. T.P. Duhart, who was not in attendance.

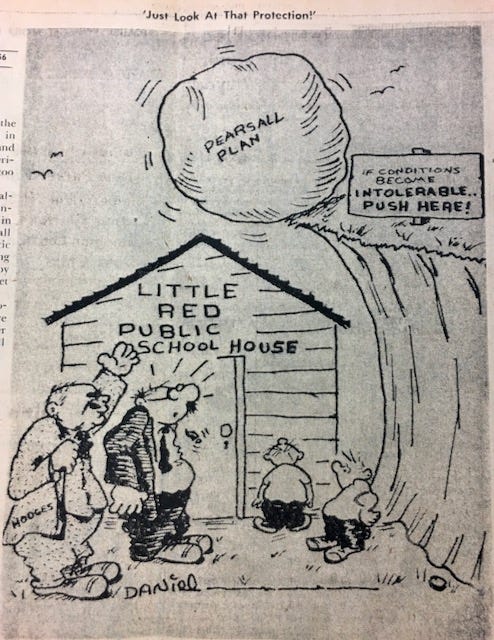

Gov. Hodges said, “We simply must provide some means of escape for the destructive pressure behind the high feelings in order to prevent the occurrence of almost certain ‘explosion’.” He called Pearsall a “safety valve” to “borrow time.” But North Carolina had no plans in development to prepare for integration, more than two years after Brown.

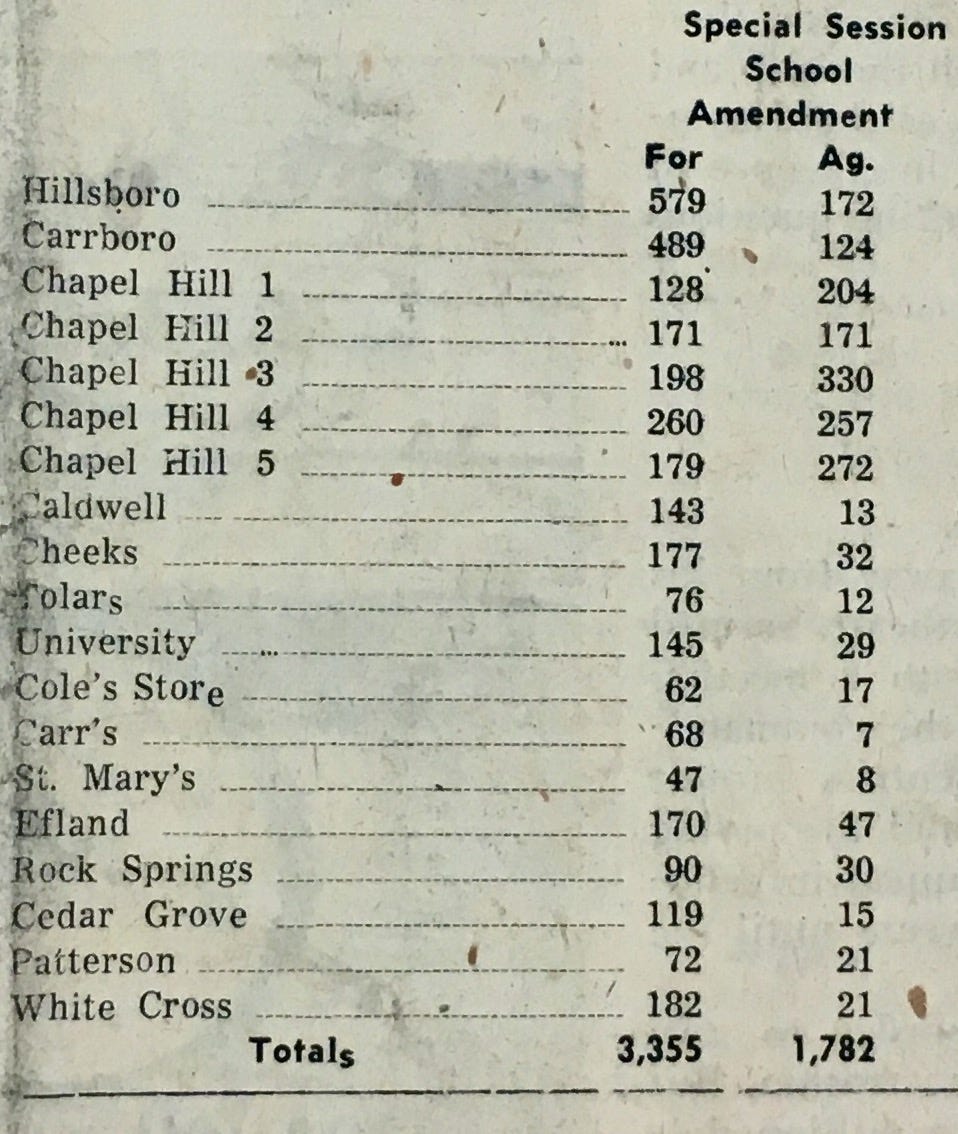

Editorial cartoon in the Chapel Hill News LeaderNORTH CAROLINA went huge for the Pearsall Plan that Saturday in an historically high turnout for a special election. Pearsall carried all 100 counties. More than 80% of people voted to add the Brown v. Board antidote to the state constitution.

In Orange County, the margin wasn’t quite as big of a blowout, but it was still 2-to-1 (65.3%). The vote was tight in Chapel Hill and Carrboro though, where 51.2% in their combined six precincts favored Pearsall.

Unofficial results for Orange County precincts in the Chapel Hill News Leader two days after the vote. The Chapel Hill and Carrboro numbers matched those reported by the Weekly a day later.While Carrboro was just as strongly in favor as the statewide electorate, at 79.8%, Chapel Hill actually went against Pearsall, with 56.9% voting no. Winston-Salem and Charlotte, with high Black voter turnout, also said no.

Likewise, the Chapel Hill opposition got a boost from a heavy Black population in Precinct 1 (northwest) and to a lesser degree in Precinct 4 (southwest), where Pearsall still won. Precinct 3 (southeast), a university residential area, went strongly against Pearsall, as did Precinct 5 (Glenwood).

For context, nearly half (45.7%) of Chapel Hill’s high school students were Black at the time, attending Lincoln High School. Today, only 9% of the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City School System’s high school students are Black or African American.

Pearsall vote aside, Chapel Hill did not fully integrate its schools until 1966, a dozen years after Brown. (The Pearsall Plan was officially ruled unconstitutional in court in 1969.) Despite the narrow margins on Pearsall locally, Chapel Hill incrementally integrated its schools with much reluctance and resistance. The eventual transition was rocky, and some Black people who were students here in those years lament still the loss of their Black educators, support systems, and traditions in the white-run schools.

Today the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools system is often regarded as the best in the state, but the legacy of its past lives on in the second-highest racial achievement gap in the United States. The gap threatens to widen with remote learning necessitated by COVID-19.

IN 1956, the anti-Brown and pro-Pearsall rhetoric was largely naked in its racist motivation. But it was also couched in reasonable explanations that gave room for plausible deniability. According to the more civility-concerned, the Pearsall Plan was needed merely to anticipate problems and legal battles sure to come, if some Black parents dared to force the issue. According to them, Pearsall simply aimed to save everyone the trouble of potential mass and lengthy school closings as events might play out in court.

Today the “school choice” and “voucher” rhetoric has adopted enough modern etiquette to leave out the explicit parts. But the inheritance of those desegregation fights are also connected to the language of real estate, whether a home is zoned for a “good” or “bad” school.

And by the way, there’s another connection to Chapel Hill through Pearsall. The work of Pauli Murray in law school later provided a framework used by Thurgood Marshall to win Brown v. Board. Murray descended from enslaved people in Chapel Hill and an enslaver who raped Murray’s great-grandmother, Harriet. Harriet worshiped in the segregated balcony of Chapel of the Cross on Franklin Street. Murray’s great-grandfather was the son of a UNC trustee. UNC rejected Murray for admittance to UNC on the basis of race.

SOURCES & CREDITS:

“A History of Private Schools & Race in the American South”: Southern Education Foundation

“Report: Public schools more segregated now than 40 years ago”: Washington Post

“The Resegregation of Jefferson County,” by Nikole Hannah-Jones: New York Times Magazine

“Hodges Faces Plan Critics; Notes Local ‘Name Callers’,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Light Voting Is Expected In County,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Hodges’ Answers Given To Audience Questions,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Local School Enrollment Totals 2,859 First Day,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Governor Answers Charges Concerning Lack Of Negro Membership On Pearsall Committee,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Will Fears Determine This Election?” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Arguments For And Against School Amendment Are Given,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 6, 1956

“Governor Defends University’s Critics, Stumps for the Passage Of Constitutional Amendments,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 7, 1956

“An Editorial: We Favor the Pearsall Plan,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 7, 1956

“Amendments Explained,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 7, 1956

“Conscientious Voting Asked,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 7, 1956

“Polling Places to Open at 6:30 A.M.,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 7, 1956

“School Enrollment Tops Last Year’s,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 7, 1956

“Extremely Heavy Electorate Gives Bare Majority Approval To Plan Here,” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 10, 1956

“What Now?” Chapel Hill News Leader, September 10, 1956

“County Goes for Pearsall, But Chapel Hill Says No,” Chapel Hill Weekly, September 11, 1956

“Pearsall Plan”: NCpedia

“Review: How school desegregation was won and lost in North Carolina”: News & Record

“A Desegregation Study of Public Schools in North Carolina,” a doctoral dissertation by Ransome E. Holcombe: ETSU

“Stymied by Segregation: How Integration Can Transform North Carolina Schools and the Lives of Its Students,” Education and Law Project, North Carolina Justice Center: ncpolicywatch.com

Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education: casetext

“Umstead, John Wesley, Jr.”: NCpedia

Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools demographic data: 2016-17 Enrollment Report

“The College-Town Achievement Gap”: The Atlantic

“Pauli Murray’s Indelible Mark On The Fight For Equal Rights”: ACLU

“Meet The Feminist Trailblazer Behind 'Brown V. Board Of Education' You've Probably Never Heard Of”: Bustle

“Pauli Murray (1910-1985)”: UNC

All newspaper images: Mike Ogle (photographed from the collections at the Chapel Hill Historical Society)